Psalm 2 Story Behind

About the Story Behind Layer

The Story Behind the Psalm shows how each part of the psalm fits together into a single coherent whole. Whereas most semantic analysis focuses on discrete parts of a text such as the meaning of a word or phrase, Story Behind the Psalm considers the meaning of larger units of discourse, including the entire psalm.

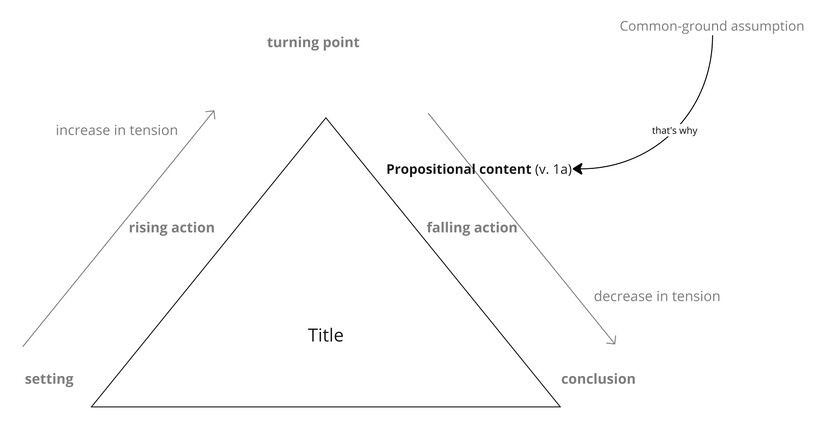

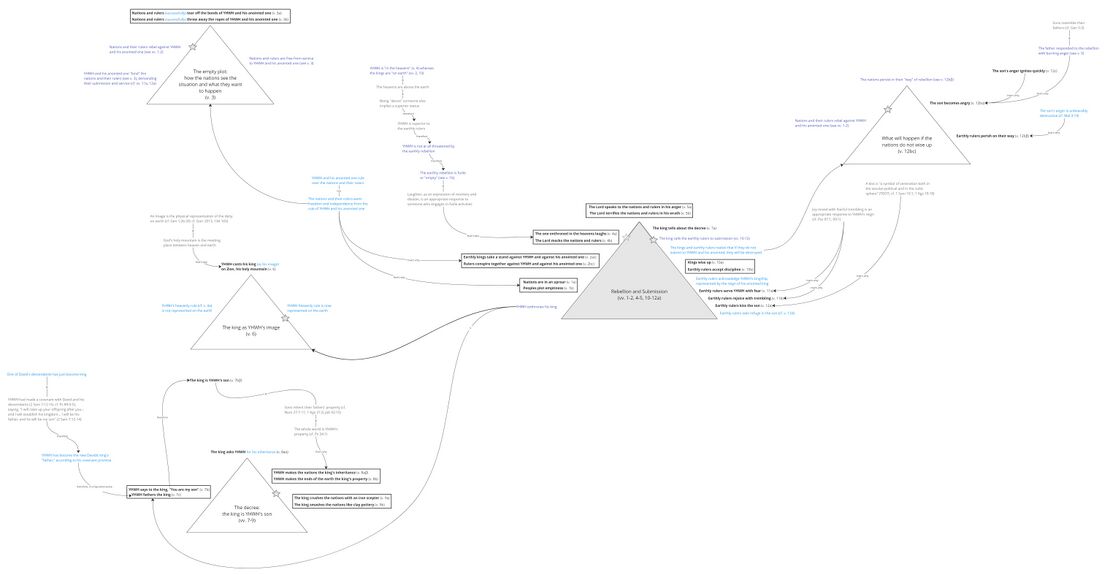

The goal of this layer is to reconstruct and visualize a mental representation of the text as the earliest hearers/readers might have conceptualized it. We start by identifying the propositional content of each clause in the psalm, and then we identify relevant assumptions implied by each of the propositions. During this process, we also identify and analyze metaphorical language (“imagery”). Finally, we try to see how all of the propositions and assumptions fit together to form a coherent mental representation. The main tool we use for structuring the propositions and assumptions is a story triangle, which visualizes the rise and fall of tension within a semantic unit. Although story triangles are traditionally used to analyze stories in the literary sense of the word, we use them at this layer to analyze “stories” in the cognitive sense of the word—i.e., a story as a sequence of propositions and assumptions that has tension.

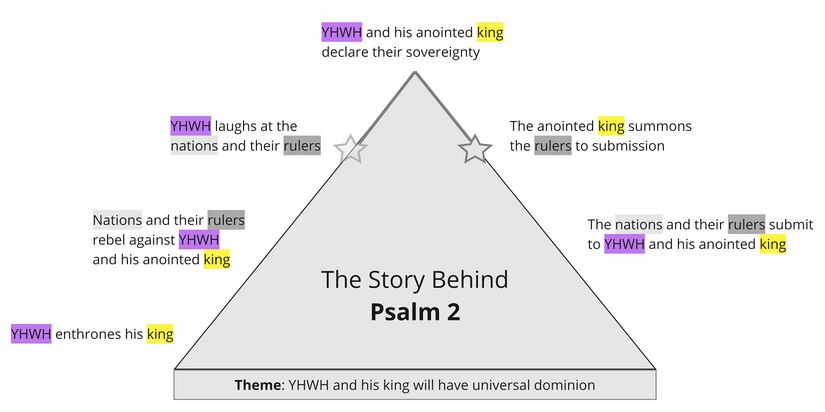

Summary Triangle

The story triangle below summarises the story of the whole psalm. We use the same colour scheme as in Participant Analysis. The star icon along the edge of the story-triangle indicates the point of the story in which the psalm itself (as a speech event) takes place. We also include a theme at the bottom of the story. The theme is the main message conveyed by the story-behind.

| Story Triangles legend | |

|---|---|

| Propositional content (verse number) | Propositional content, the base meaning of the clause, is indicated by bold black text. The verse number immediately follows the correlating proposition in black text inside parentheses. |

| Common-ground assumption | Common-ground assumptions[1] are indicated by gray text. |

| Local-ground assumption | Local-ground assumptions[2] are indicated by dark blue text. |

| Playground assumption | Playground assumptions[3] are indicated by light blue text. |

| The point of the story at which the psalm takes place (as a speech event) is indicated by a gray star. | |

| If applicable, the point of the story at which the psalm BEGINS to take place (as a speech event) is indicated with a light gray star. A gray arrow will travel from this star to the point at which the psalm ends, indicated by the darker gray star. | |

| A story that repeats is indicated by a circular arrow. This indicates a sequence of either habitual or iterative events. | |

| A story or event that does not happen or the psalmist does not wish to happen is indicated with a red X over the story triangle. | |

| Connections between propositions and/or assumptions are indicated by black arrows with small text indicating how the ideas are connected. | |

| Note: In the Summary triangle, highlight color scheme follows the colors of participant analysis. | |

Background ideas

Following are the common-ground assumptionsCommon-ground assumptions include information shared by the speaker and hearers. In our analysis, we mainly use this category for Biblical/Ancient Near Eastern background. which are the most helpful for making sense of the psalm.

- YHWH made a covenant with David and his descendants (2 Sam 7:12-16; cf. Ps 89:4-5), saying, "I will raise up your offspring after you... and I will establish his kingdom... I will be his father, and he will be my son" (2 Sam 7:12-14).

- Sons inherit their fathers' property (cf. Num 27:7-11; 1 Kgs 21:3; Job 42:15).

- YHWH chose Zion, "the city of David" (2 Sam 5:7), as his holy mountain (Ps 132:13-14).

- A mountain is a place where heaven (cf. v. 4a) and earth (cf. v. 2a) meet and thus a place where people experience God's presence and power (see e.g., Gen 22; Exod 3:1-2; 19; cf. Matt 17:1-8).

- The king is the "image" of his god, the deity's earthly representative (cf. Gen 1:26-28; cf. Garr 2013, 136-165).

- Lesser kings (vassals) frequently rebelled against greater rulers (suzerains; Ringgren 1983, 91-95), especially when the greater kingdom experienced a change in kingship (Hilber 2009, 320). In the Neo-Assyrian period (early 10th–7th centuries BC), accounts of withstanding a rebellion were a regular part of inscriptions and palace decorations which served to confirm the divine appointment of a king (Radner 2016, 46, 54).

- A kiss is "a symbol of veneration both in the secular-political and in the cultic sphere" (TDOT; cf. 1 Sam 10:1; 1 Kgs 19:18).

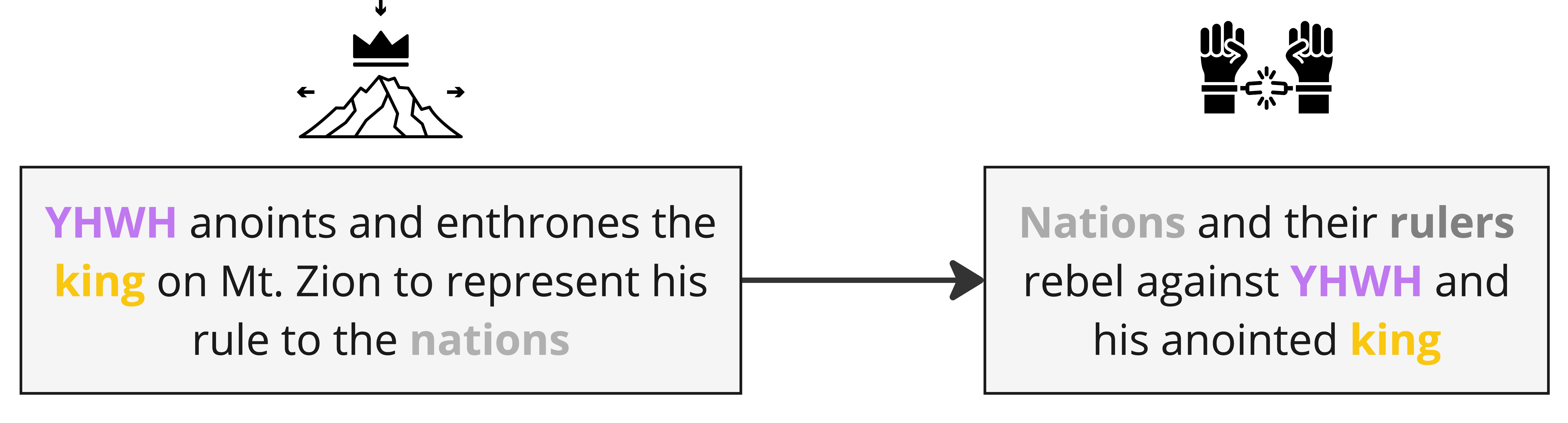

Background situation

The background situation is the series of events leading up to the time in which the psalm is spoken. These are taken from the story triangle – whatever lies to the left of the star icon.

Expanded Paraphrase

The expanded paraphrase seeks to capture the implicit information within the text and make it explicit for readers today. It is based on the CBC translation and uses italic text to provide the most salient background information, presuppositions, entailments, and inferences.

| Expanded paraphrase legend | |

|---|---|

| Close but Clear (CBC) translation | The CBC, our close but clear translation of the Hebrew, is represented in bold text. |

| Assumptions | Assumptions which provide background information, presuppositions, entailments, and inferences are represented in italics. |

| Text (Hebrew) | Verse | Expanded Paraphrase |

|---|---|---|

| לָ֭מָּה רָגְשׁ֣וּ גוֹיִ֑ם וּ֝לְאֻמִּ֗ים יֶהְגּוּ־רִֽיק׃ | 1 | YHWH and his anointed king rule over the nations and their rulers. But the nations and their rulers want freedom and independence from the imperial rule of YHWH and his anointed one, and so they are attempting to rebel. But there is no point! They will certainly be defeated. Why do they even bother? Why are nations in an uproar, like an agitated crowd or like a turbulent sea, and [why] do peoples make plots that result only in emptiness? |

| יִ֥תְיַצְּב֨וּ ׀ מַלְכֵי־אֶ֗רֶץ וְרוֹזְנִ֥ים נֽוֹסְדוּ־יָ֑חַד | 2 | [Why] do earthly kings who govern the nations as vassals to YHWH and his king take a stand against their suzerains, and [why] have rulers conspired together against YHWH and against his king whom he anointed as the one to rule his people? |

| עַל־יְ֝הוָה וְעַל־מְשִׁיחֽוֹ׃ נְֽ֭נַתְּקָה אֶת־מֽוֹסְרוֹתֵ֑ימוֹ | 3 | The rebels say, "Let's stop serving them! Let's tear off their bonds and throw their ropes away from us! Let's achieve independence!" |

| וְנַשְׁלִ֖יכָה מִמֶּ֣נּוּ עֲבֹתֵֽימוֹ׃ יוֹשֵׁ֣ב בַּשָּׁמַ֣יִם יִשְׂחָ֑ק | 4 | The one enthroned in the heavens, far above the earthly kings, is not threatened by their rebellion. Instead, he laughs at them, an expression of mockery and disdain. The all-powerful Lord whom they ought to be serving mocks them. |

| אֲ֝דֹנָ֗י יִלְעַג־לָֽמוֹ׃ אָ֤ז יְדַבֵּ֣ר אֵלֵ֣ימוֹ בְאַפּ֑וֹ | 5 | Then he speaks to them in his anger and terrifies them in his wrath. |

| וּֽבַחֲרוֹנ֥וֹ יְבַהֲלֵֽמוֹ׃ וַ֭אֲנִי נָסַ֣כְתִּי מַלְכִּ֑י | 6 | He says in response to their words (v. 3): "You can plot all you like, but it will not work. I have poured out my king as my image, just as a craftsman pours liquid metal into a mold to make an image, and I have placed him on Zion, the city of David, my holy mountain, the place where heaven and earth meet, to represent my heavenly rule on the earth. Nothing that you do can alter this reality." |

| עַל־צִ֝יּ֗וֹן הַר־קָדְשִֽׁי׃ אֲסַפְּרָ֗ה אֶֽ֫ל חֹ֥ק | 7 | Listen up, you rebellious nations! I the king whom YHWH anointed and cast as his image, will tell about the covenant YHWH made with my father, David, which he has confirmed to me as a decree, a decree that you must heed; YHWH said to me on the day of my enthronement, "You are my son. You resemble me in terms of character, you represent my rule, and you will always receive my paternal care. With this speech, I hereby father you today, on the day of your enthronement, causing you to be born into a royal existence, thus fulfilling what I promised your father, David, when I told him, 'I will raise up your offspring after you... and I will establish his kingdom... I will become his father, and he will become my son' (2 Sam 7:12-14). |

| יְֽהוָ֗ה אָמַ֘ר אֵלַ֥י בְּנִ֥י אַ֑תָּה אֲ֝נִ֗י הַיּ֥וֹם יְלִדְתִּֽיךָ׃ | 8 | Ask me, my son, for your inheritance, and I will make nations your inheritance and the ends of the earth your property. For the whole world is mine, and you, my only son, will inherit it all. |

| שְׁאַ֤ל מִמֶּ֗נִּי וְאֶתְּנָ֣ה ג֭וֹיִם נַחֲלָתֶ֑ךָ וַ֝אֲחֻזָּתְךָ֗ אַפְסֵי־אָֽרֶץ׃ | 9 | If they try to rebel against your rule, I will be with you to strengthen you, and you will crush them with an iron scepter and smash them like fragile clay pottery that, once it is smashed, cannot be put back together." |

| תְּ֭רֹעֵם בְּשֵׁ֣בֶט בַּרְזֶ֑ל כִּכְלִ֖י יוֹצֵ֣ר תְּנַפְּצֵֽם׃ | 10 | And now, you foolish kings, having heard YHWH's decree, wise up! Accept YHWH's discipline and submit to him, earthly rulers! |

| וְ֭עַתָּה מְלָכִ֣ים הַשְׂכִּ֑ילוּ הִ֝וָּסְר֗וּ שֹׁ֣פְטֵי אָֽרֶץ׃ | 11 | Serve YHWH, the heavenly Lord, with fear. Live according to his requirements, especially his "decree" (v. 7). Celebrate his rule and rejoice at his good kingship, but do so with fear and trembling, for he can destroy you in a moment if you step out of line! |

| עִבְד֣וּ אֶת־יְהוָ֣ה בְּיִרְאָ֑ה וְ֝גִ֗ילוּ בִּרְעָדָֽה׃ נַשְּׁקוּ־בַ֡ר פֶּן־יֶאֱנַ֤ף ׀ וְתֹ֬אבְדוּ דֶ֗רֶךְ | 12 | Kiss the son as a sign of honor and submission, or else he will become angry and you will perish in your way of rebellion that you have chosen to walk, for his anger easily ignites and burns everything in its path . You will not stand a chance if you oppose him! But if you submit to him, then you and your peoples will flourish under his righteous rule. Happy are all who take refuge in him, for he is a good king who takes care of his people! |

There are currently no Imagery Tables available for this psalm.

Bibliography

- Andrason, Alexander. 2012. “Making It Sound - The Performative Qatal and Its Explanation.” The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 12 (October): 1–58.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Cook, John A. 2024. The Biblical Hebrew Verb: A Linguistic Introduction. Learning Biblical Hebrew. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

- Craigie, Peter C. 1983. Psalms 1–50. WBC 19. Waco, TX: Word.

- Creach, Jerome F. D. 1996. Yahweh as Refuge and the Editing of the Hebrew Psalter. A&C Black.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1996. “Psalms.” In Commentary on the Old Testament, translated by James Martin. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson.

- Eaton, J. H. 1975. Kingship and the Psalms. London: S.C.M. Press.

- Fokkelman, J. P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Hermeneutics and Structural Analysis. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum.

- Garr, W. Randall. 2003. In His Own Image and Likeness : Humanity, Divinity, and Monotheism. Leiden ; Boston: Brill.'

- Gentry, Peter J. 1998. “The System of the Finite Verb in Classical Hebrew.” Hebrew Studies 39:7–39.

- Gesenius, W. Donner, H. Rüterswörden, U. Renz, J. Meyer, R. (eds.). 2013. Hebräisches und aramäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament. 18. Auflage Gesamtausgabe. Berlin: Springer.

- Goldingay, John. 2006. Psalms: Psalms 1–41. Vol. 1. BCOT. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

- Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm. 1863. Commentary on the Psalms. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- Herion, Gary A. 1992. “Wrath of God (OT).” In Anchor Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 6:989–96. New York: Doubleday.

- Hilber, John. 2009. “Psalms.” In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary: The Minor Prophets, Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, edited by John Walton. Vol. 5. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Hoffmeier, James. 1994. “The King as Son of God in Egypt and Israel.” The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 24:28–38.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 1993. Die Psalmen I: Psalm 1–50. Neue Echter Bibel. Würzburg: Echter.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1855. Die Psalmen. Vol. 1. Gotha: Friedrich Andreas Perthes.

- Ibn Ezra. Ibn Ezra on Psalms.

- Jenni, Ernst. 2000. Die hebräischen Präpositionen Band 3: Die Präposition Lamed. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Jones, G H. 1965. “The Decree of Yahweh (Ps. II 7).” Vetus Testamentum 15 (3): 336–44.

- Kim, Young Bok. 2023. Hebrew Forms of Address: A Sociolinguistic Analysis. Atlanta: SBL Press. vvo.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2006. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter. Vol. 1. 3 vols. Oudtestamentische Studiën 53. Leiden: Brill.

- Malbim. Malbim on Psalms.

- Mena, Andrea K. 2012. “The Semantic Potential of עַל in Genesis, Psalms, and Chronicles.” MA Thesis, Stellenbosch University.

- Murnane, William Joseph, and Edmund S. Meltzer. 1995. Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt. Writings from the Ancient World 5. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- Niccacci, Alviero. 2006. “The Biblical Hebrew Verbal System in Poetry.” In Biblical Hebrew in Its Northwest Semitic Setting: Typological and Historical Perspectives, edited by Steven E. Fassberg and Avi Hurvitz, 247–68. Publication of the Institute for Advanced Studies, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Magnes Press.

- Penney, Jason. 2023. “A Typological Examination of Pluractionality in the Biblical Hebrew Piel.” MA, Dallas: Dallas International University.

- Poole, Matthew. 1678. Synopsis Criticorum Aliorumque Sacrae Scripturae. Vol. 2: a Jobi ad Canticum Canticorum.

- Raabe, Paul. 1991. “Deliberate Ambiguity in the Psalter.” Journal of Biblical Literature 110 (2): 213–27.

- Radak. Radak on Psalms.

- Radner, Karen. 2016. “3 Revolts in the Assyrian Empire: Succession Wars, Rebellions Against a False King and Independence Movements.” In Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East, edited by John J. Collins and J.G. Manning, 39–54. Brill.

- Rashi. Rashi on Psalms.

- Ringgren, Helmer. 1983. “Psalm 2 and Bēlit’s Oracle for Ashurbanipal.” In The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth, edited by Carol L Meyers and M. O’Connor, 91–95. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Robar, Elizabeth. 2015. The Verb and the Paragraph in Biblical Hebrew: A Cognitive-Linguistic Approach. Vol. 78. Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill.

- Robar, Elizabeth. 2022. “Morphology and Markedness: On Verb Switching in Hebrew Poetry: SBL Annual Meeting 2020 Linguistics and Biblical Hebrew Seminar: Typological and Grammatical Categorization of Biblical Hebrew.” Journal for Semitics 30 (2).

- Tatu, Silviu. 2006. “The Rhetorical Interpretation of the Yiqtol//Qatal (Qatal//Yiqtol) Verbal Sequence in Classical Hebrew Poetry and Its Research History.” Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies 23 (1): 17–23.

- Tsumura, David Toshio. 2023. Vertical Grammar of Parallelism in Biblical Hebrew. Ancient Israel and Its Literature 47. Atlanta: SBL Press.

- Victor, Peddi. 1966. “Note on Choq in the Old Testament.” Vetus Testamentum 16 (3): 358–61.

- Walton, John H. 2018. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Second edition. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group.

- Weber, Beat. 2016. Werkbuch Psalmen. 1: Die Psalmen 1 bis 72. Zweite aktualisierte Auflage. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

Footnotes

- ↑ Common-ground assumptions include information shared by the speaker and hearers. In our analysis, we mainly use this category for Biblical/ANE background - beliefs and practices that were widespread at this time and place. This is the background information necessary for understanding propositions that do not readily make sense to those who are so far removed from the culture in which the proposition was originally expressed.

- ↑ Local-ground assumptions are those propositions which are necessarily true if the text is true. They include both presuppositions and entailments. Presuppositions are those implicit propositions which are assumed to be true by an explicit proposition. Entailments are those propositions which are necessarily true if a proposition is true.

- ↑ Whereas local-ground assumptions are inferences which are necessarily true if the text is true, play-ground assumptions are those inferences which might be true if the text is true.