Psalm 31 Discourse

About the Discourse Layer

Our Discourse Layer includes four additional layers of analysis:

- Participant analysis

- Macrosyntax

- Speech act analysis

- Emotional analysis

For more information on our method of analysis, click the expandable explanation button at the beginning of each layer.

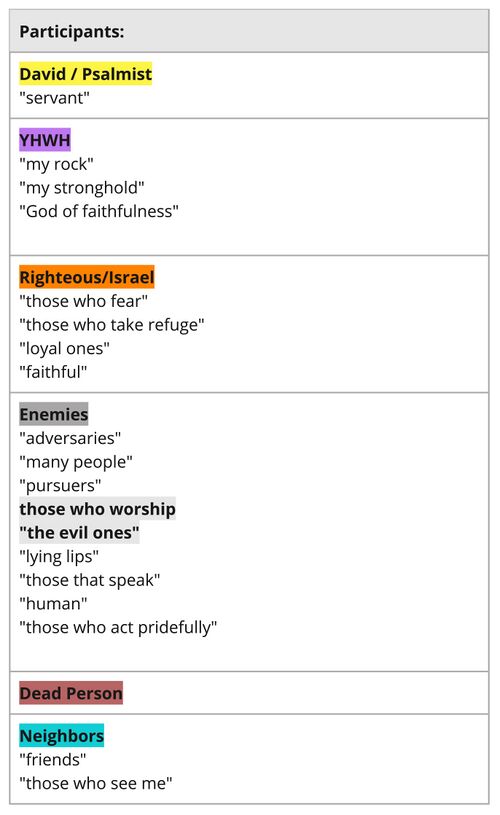

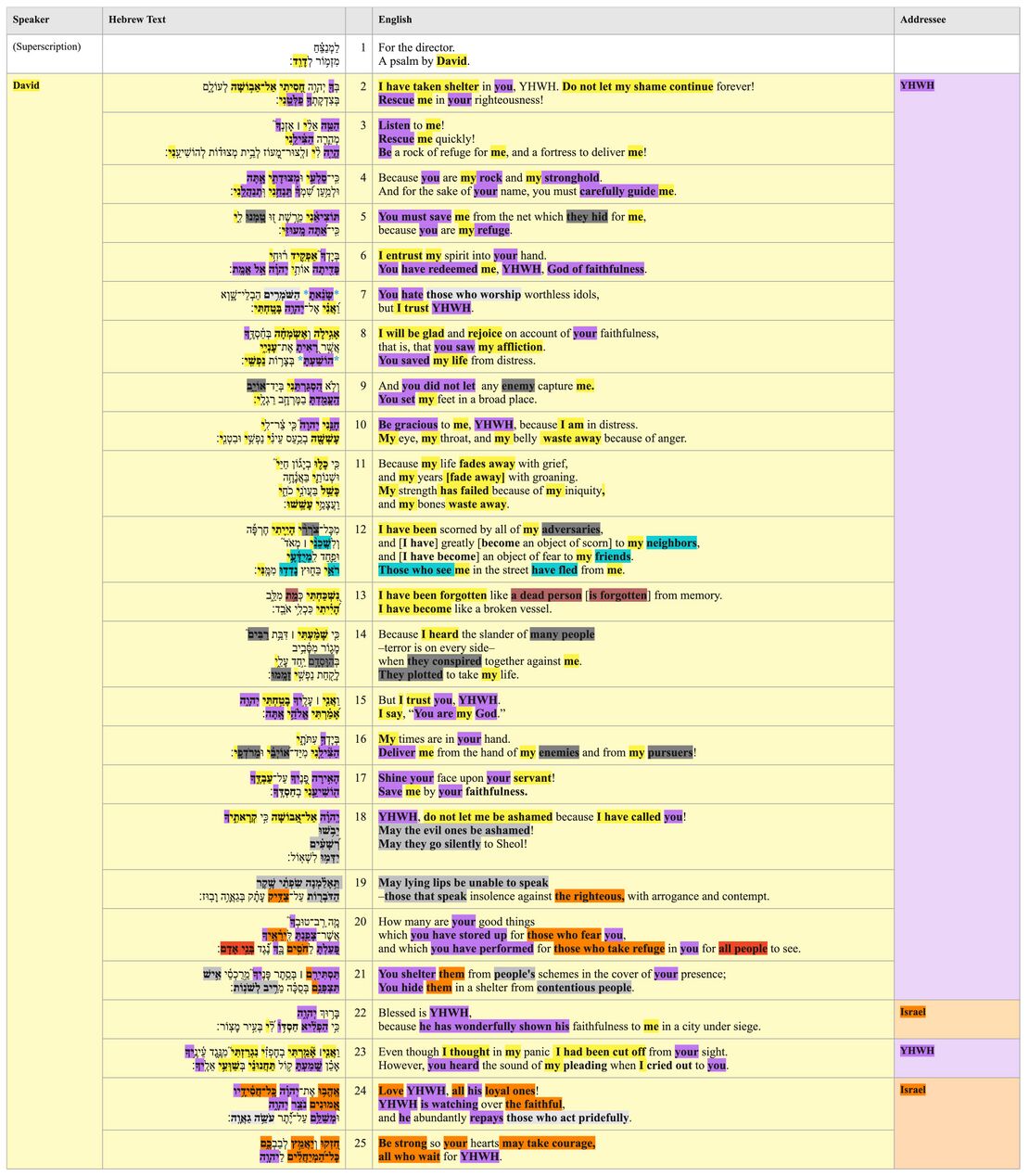

Participant Analysis

Participant Analysis focuses on the characters in the psalm and asks, “Who are the main participants (or characters) in this psalm, and what are they saying or doing? It is often helpful for understanding literary structure, speaker identification, etc.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Participant Analysis Creator Guidelines.

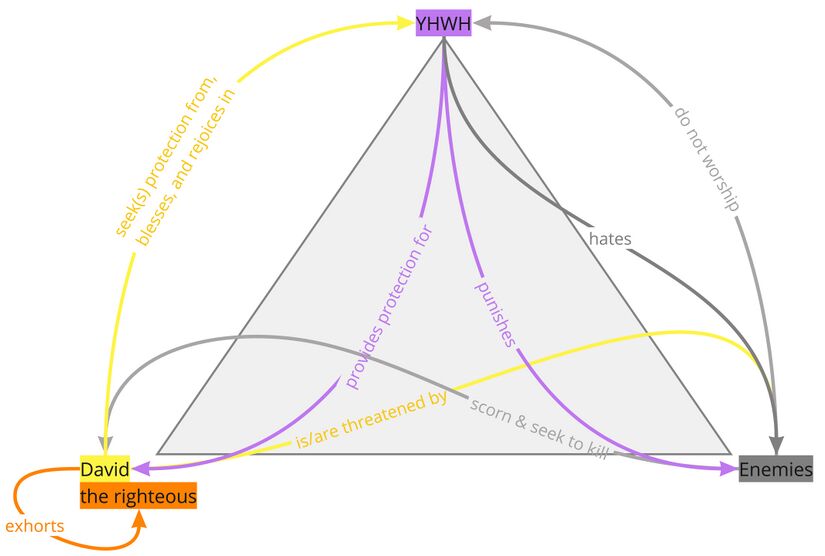

Participant Relations Diagram

The relationships among the participants may be abstracted and summarized as follows:

Macrosyntax

The macrosyntax layer rests on the belief that human communicators desire their addressees to receive a coherent picture of their message and will cooperatively provide clues to lead the addressee into a correct understanding. So, in the case of macrosyntax of the Psalms, the psalmist has explicitly left syntactic clues for the reader regarding the discourse structure of the entire psalm. Here we aim to account for the function of these elements, including the identification of conjunctions which either coordinate or subordinate entire clauses (as the analysis of coordinated individual phrases is carried out at the phrase-level semantics layer), vocatives, other discourse markers, direct speech, and clausal word order.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Macrosyntax Creator Guidelines.

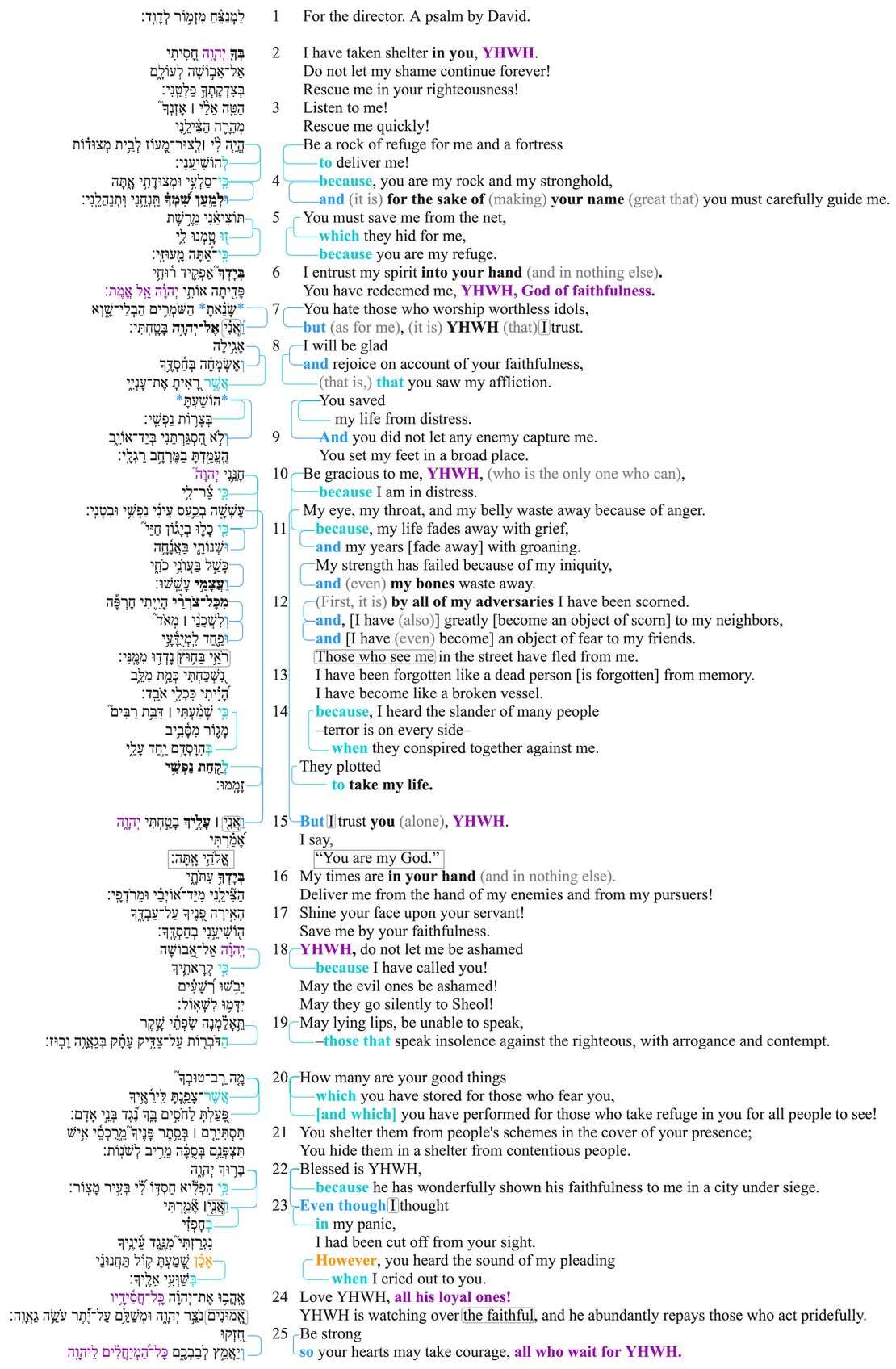

Macrosyntax Diagram

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[1] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[2] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Speech Act Analysis

The Speech Act layer presents the text in terms of what it does, following the findings of Speech Act Theory. It builds on the recognition that there is more to communication than the exchange of propositions. Speech act analysis is particularly important when communicating cross-culturally, and lack of understanding can lead to serious misunderstandings, since the ways languages and cultures perform speech acts varies widely.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Speech Act Analysis Creator Guidelines.

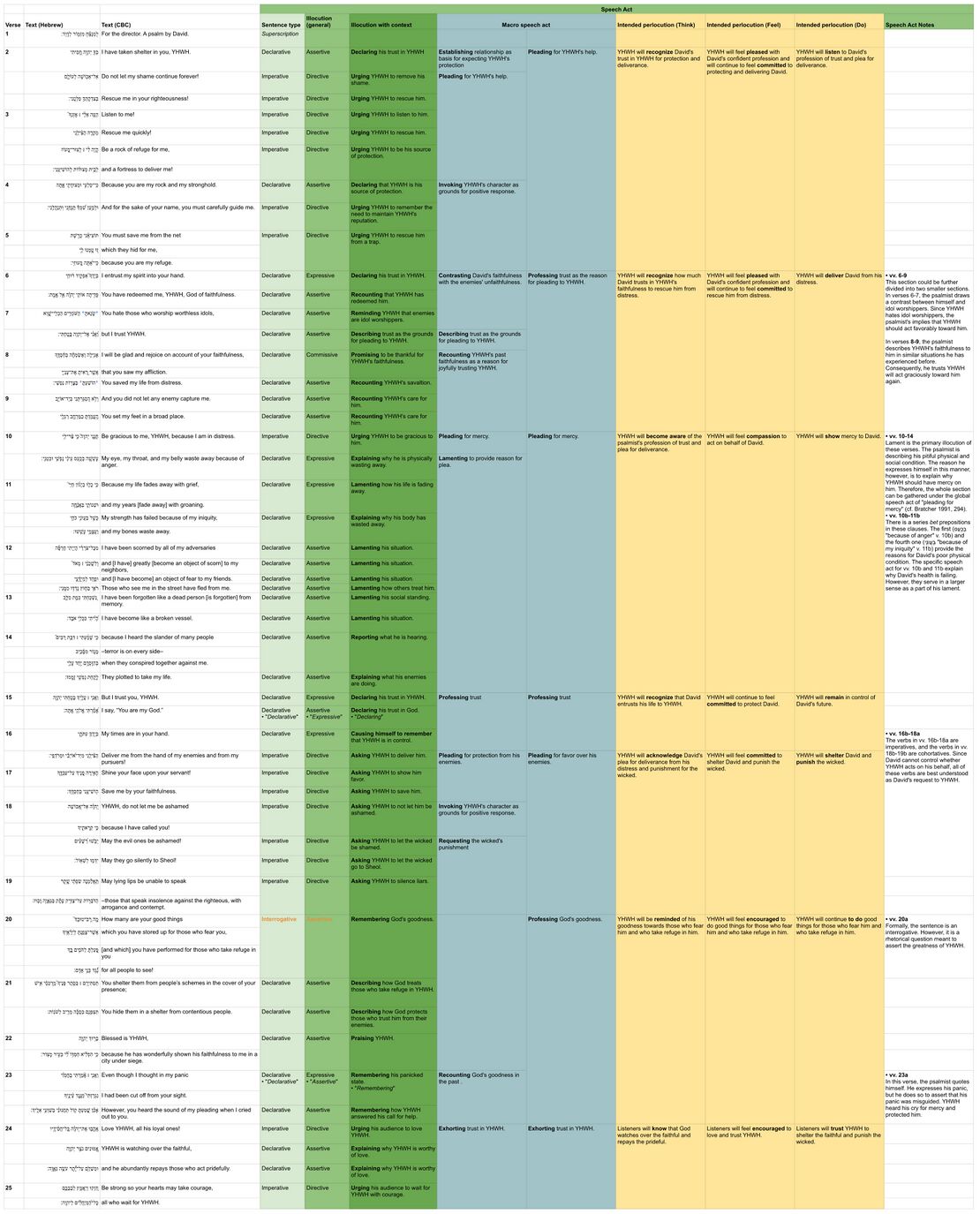

Summary Visual

Speech Act Chart

The following chart is scrollable (left/right; up/down).

| Verse | Hebrew | CBC | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) |

| Verse number and poetic line | Hebrew text | English translation | Declarative, Imperative, or Interrogative Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

Assertive, Directive, Expressive, Commissive, or Declaratory Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

More specific illocution type with paraphrased context | Illocutionary intent (i.e. communicative purpose) of larger sections of discourse These align with the "Speech Act Summary" headings |

What the speaker intends for the address to think | What the speaker intends for the address to feel | What the speaker intends for the address to do |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

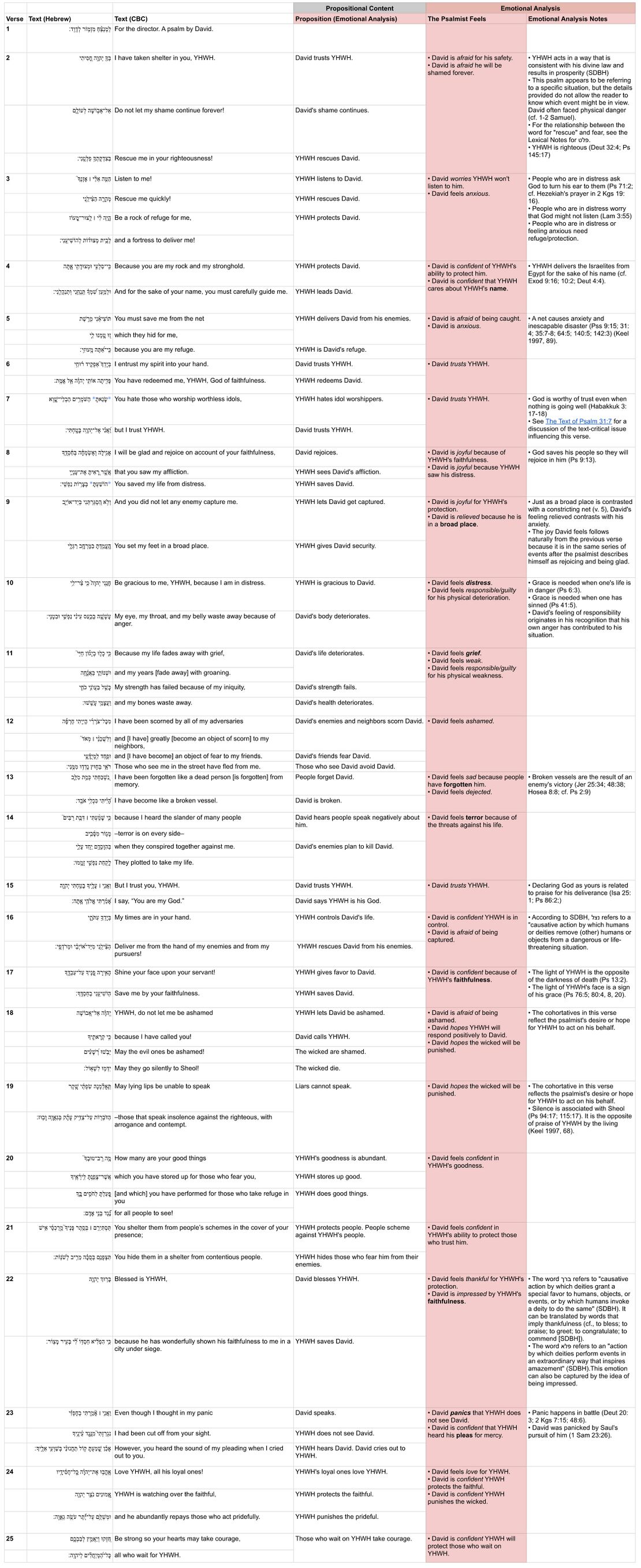

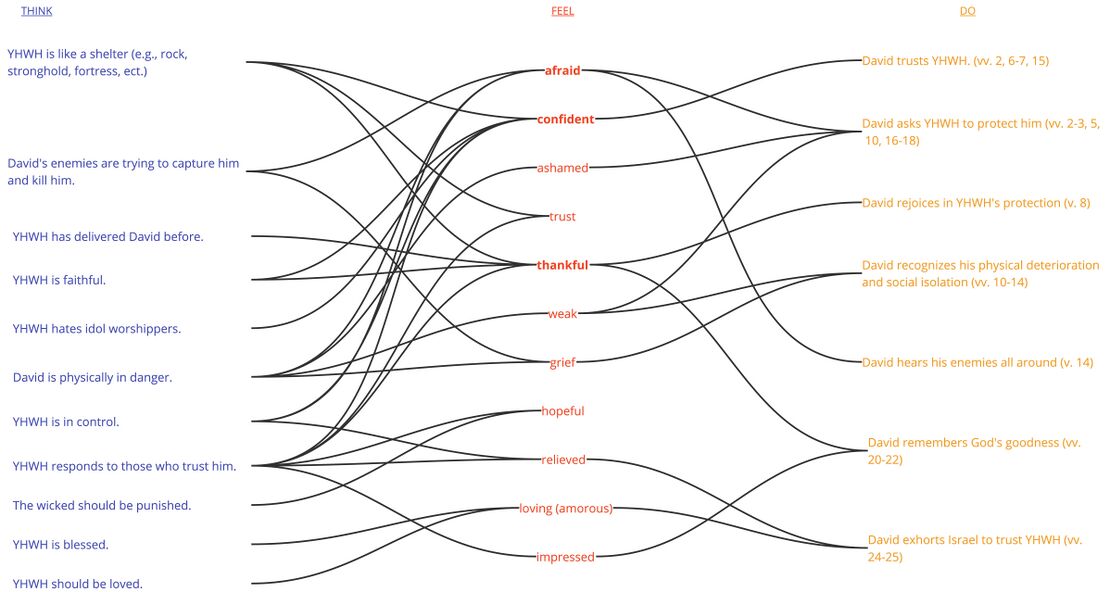

Emotional Analysis

This layer explores the emotional dimension of the biblical text and seeks to uncover the clues within the text itself that are part of the communicative intent of its author. The goal of this analysis is to chart the basic emotional tone and/or progression of the psalm.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Emotional Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Emotional Analysis Chart

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Summary Visual

Bibliography

- Barthélemy, Dominique. 2005. Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament. Vol. Tome 4: Psaumes. Fribourg, Switzerland: Academic Press.

- Basson, A. 2005. “‘You Are My Rock and Fortress’. Refuge Metaphors in Psalm 31. a Perspective from Cognitive Metaphor Theory.” Acta Theologica 25 (2): 1–17.

- Bratcher, Robert G., and William D. Reyburn. 1991. A Handbook on Psalms. UBS Handbook Series. New York: United Bible Societies.

- Briggs, Charles A., and Emilie Briggs. 1906. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Vol. 1. ICC. Edinburgh: T & T Clark.

- Brockington, L. H. 1973. The Hebrew Text of the Old Testament: The Readings Adopted by the Translators of the New English Bible.

- Brueggemann, Walter, and W. H. Bellinger. 2014. Psalms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Calvin, John. n.d. Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Translated by James Anderson. Grand Rapids: Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- Cohen, Chaim. 2004. “The Enclitic-Mem in Biblical Hebrew: Its Existence and Initial Discovery.” In Sefer Moshethe Moshe Weinfeld Jubilee Volume: Studies in the Bible and the Ancient Near East, Qumran, and Post-Biblical Judaism, 231–60. Winona Lake, Ind.

- Companioni, Carrera, and Roberto Adrian. 2022. “The Mercati Fragments: A New Edition of Rahlfs 1098,” December.

- Conybeare, F. C. (Frederick Cornwallis). 1905. Selections from the Septuagint: According to the Text of Swete. Boston : Ginn & Company.

- Craigie, Peter C. 1983. Psalms 1–50. WBC 19. Waco, TX: Word.

- Dahood, Mitchell edt trl. 1966. Psalms. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday.

- DeClaisse-Walford, Nancy L., Rolf A. Jacobson, and Beth LaNeel Tanner. 2014. The Book of Psalms. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Delekat, L. 1964. “Zum Hebräischen Wörterbuch.” Vetus Testamentum 14 (1): 7–66.

- Dion, Paul-Eugène. 1987. “Strophic Boundaries and Rhetorical Structure in Psalm 31.” Église et Théologie 18 (2): 183–92.

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 2: 85 Psalms and Job 4–14). Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Van Gorcum.

- Hummel, Horace D. 1957. “Enclitic Mem in Northwest Semitic, Especially Hebrew.” Journal of Biblical Literature 76 (2): 85–104.

- Laberge, Léo. 1985. “A Literary Analysis of Psalm 31.” Église et Théologie 16 (2): 147–68.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2006. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter. Vol. 1. 3 vols. Oudtestamentische Studiën 53. Leiden: Brill.

- Mena, Andrea K. 2012. “The Semantic Potential of ’al in Genesis, Psalms, and Chronicles.” Stellenbosch : Stellenbosch University.

- Merwe, C H J van der. 1993. “Old Hebrew Particles and the Interpretation of Old Testament Texts.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 18 (60): 27–44.

- Miller, Cynthia L. 2010. “Vocative Syntax in Biblical Hebrew Prose and Poetry: A Preliminary Analysis.” Journal of Semitic Studies 55 (2): 347–64.

- Potgieter, J. Henk. 2012. “‘David’ in Consultation with the Prophets: The Intertextual Relationship of Psalm 31 with the Books of Jonah and Jeremiah.” Old Testament Essays 25 (1): 115–26.

- Roberts, J J M. 1975. “Niskahtî--Millēb, Ps 31:13: Vetus Testamentum.” Vetus Testamentum 25 (4): 797–801.

- Villanueva, Federico G. 2016. Psalms 1-72. Carlisle, England: Langham Global Library.

Footnotes

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.