Psalm 38 Story Behind

About the Story Behind Layer

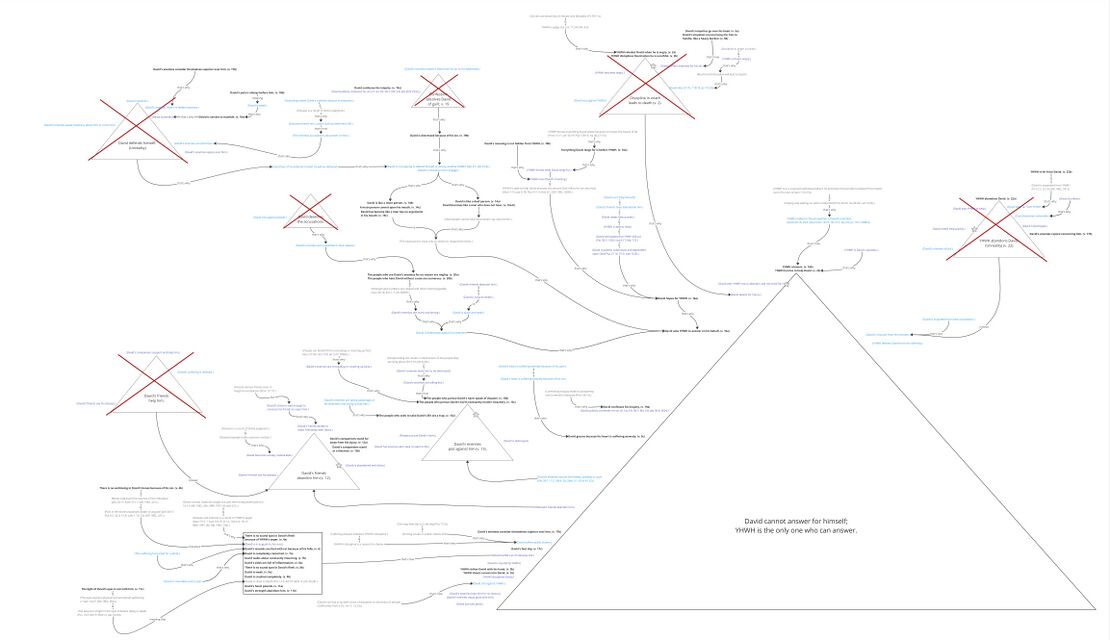

The Story Behind the Psalm shows how each part of the psalm fits together into a single coherent whole. Whereas most semantic analysis focuses on discrete parts of a text such as the meaning of a word or phrase, Story Behind the Psalm considers the meaning of larger units of discourse, including the entire psalm.

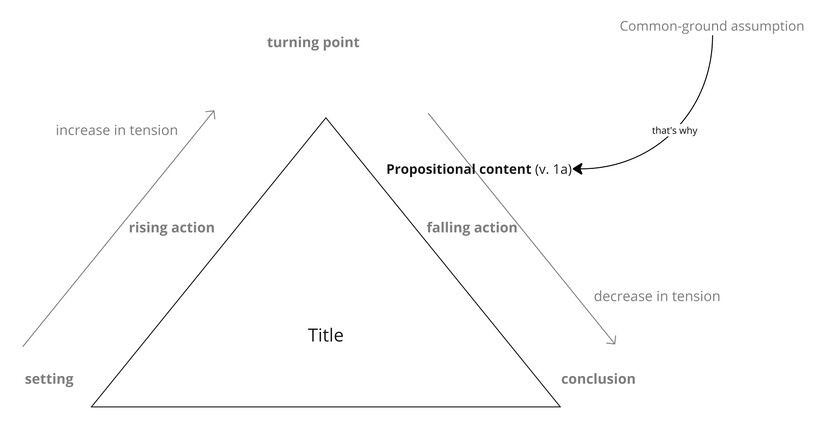

The goal of this layer is to reconstruct and visualize a mental representation of the text as the earliest hearers/readers might have conceptualized it. We start by identifying the propositional content of each clause in the psalm, and then we identify relevant assumptions implied by each of the propositions. During this process, we also identify and analyze metaphorical language (“imagery”). Finally, we try to see how all of the propositions and assumptions fit together to form a coherent mental representation. The main tool we use for structuring the propositions and assumptions is a story triangle, which visualizes the rise and fall of tension within a semantic unit. Although story triangles are traditionally used to analyze stories in the literary sense of the word, we use them at this layer to analyze “stories” in the cognitive sense of the word—i.e., a story as a sequence of propositions and assumptions that has tension.

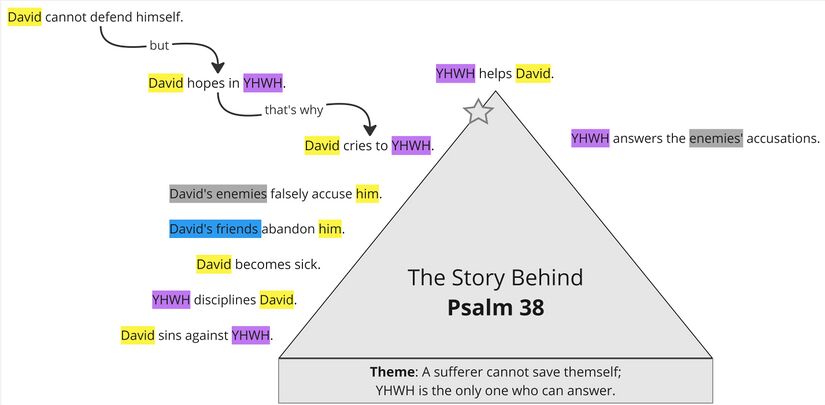

Summary Triangle

The story triangle below summarises the story of the whole psalm. We use the same colour scheme as in Participant Analysis. The star icon along the edge of the story-triangle indicates the point of the story in which the psalm itself (as a speech event) takes place. We also include a theme at the bottom of the story. The theme is the main message conveyed by the story-behind.

| Story Triangles legend | |

|---|---|

| Propositional content (verse number) | Propositional content, the base meaning of the clause, is indicated by bold black text. The verse number immediately follows the correlating proposition in black text inside parentheses. |

| Common-ground assumption | Common-ground assumptions[1] are indicated by gray text. |

| Local-ground assumption | Local-ground assumptions[2] are indicated by dark blue text. |

| Playground assumption | Playground assumptions[3] are indicated by light blue text. |

| The point of the story at which the psalm takes place (as a speech event) is indicated by a gray star. | |

| If applicable, the point of the story at which the psalm BEGINS to take place (as a speech event) is indicated with a light gray star. A gray arrow will travel from this star to the point at which the psalm ends, indicated by the darker gray star. | |

| A story that repeats is indicated by a circular arrow. This indicates a sequence of either habitual or iterative events. | |

| A story or event that does not happen or the psalmist does not wish to happen is indicated with a red X over the story triangle. | |

| Connections between propositions and/or assumptions are indicated by black arrows with small text indicating how the ideas are connected. | |

| Note: In the Summary triangle, highlight color scheme follows the colors of participant analysis. | |

Background ideas

Following are the common-ground assumptionsCommon-ground assumptions include information shared by the speaker and hearers. In our analysis, we mainly use this category for Biblical/Ancient Near Eastern background. which are the most helpful for making sense of the psalm.

- Sickness is a common form of divine punishment (Ps 6:1-2, 102:3-4, 10-11; Keel 1997, 80). YHWH is the ultimate judge and so has the right to condemn or acquit David accordingly.

- Sickness is sometimes used metaphorically to describe spiritual or mental suffering.

- Disease could lead to ostracism because it is a result of divine judgment and because of the Levitical laws concerning some diseases that require the sick person to leave camp (Ryken et al. 1982, 2182; Lev 13:46; 14:19-20; see John 9:1).

Background situation

The background situation is the series of events leading up to the time in which the psalm is spoken. These are taken from the story triangle – whatever lies to the left of the star icon.

Expanded Paraphrase

The expanded paraphrase seeks to capture the implicit information within the text and make it explicit for readers today. It is based on the CBC translation and uses italic text to provide the most salient background information, presuppositions, entailments, and inferences.

| Expanded paraphrase legend | |

|---|---|

| Close but Clear (CBC) translation | The CBC, our close but clear translation of the Hebrew, is represented in bold text. |

| Assumptions | Assumptions which provide background information, presuppositions, entailments, and inferences are represented in italics. |

| Text (Hebrew) | Verse | Expanded Paraphrase |

|---|---|---|

| מִזְמ֖וֹר לְדָוִ֣ד לְהַזְכִּֽיר׃ | 1 | A psalm. By David. To bring David to God's remembrance so that he will act and help. |

| יְֽהוָ֗ה אַל־בְּקֶצְפְּךָ֥ תוֹכִיחֵ֑נִי | 2 | YHWH, I have sinned, and I deserve to be rebuked and disciplined. But I ask that you do not rebuke me as a judge when you're angry, or discipline me when you're wrathful so that I do not die! |

| כִּֽי־חִ֭צֶּיךָ נִ֣חֲתוּ בִ֑י וַתִּנְחַ֖ת עָלַ֣י יָדֶֽךָ׃ | 3 | For you have disciplined me as if with intense sickness. Your arrows which bring death and sickness have been shot into me in order to discipline me, and your hand has struck me and so I feel as if I have been injured. |

| אֵין־מְתֹ֣ם בִּ֭בְשָׂרִי מִפְּנֵ֣י זַעְמֶ֑ךָ אֵין־שָׁל֥וֹם בַּ֝עֲצָמַ֗י מִפְּנֵ֥י חַטָּאתִֽי׃ | 4 | There is no sound spot in my flesh because of your anger and so every part of me is affected by your discipline and wrath. There is no well-being in my bones, the very core of my being, because of my sin, the reason why you are angry and why I am being disciplined and therefore the reason why I suffer. Therefore the very core of my being is in anguish. |

| כִּ֣י עֲ֭וֺנֹתַי עָבְר֣וּ רֹאשִׁ֑י | 5 | For my iniquities have fully gone over my head, overwhelming me. Like a heavy burden, they are utterly too heavy for me to handle even though I have tried. Without help, I will be crushed by them and die. |

| הִבְאִ֣ישׁוּ נָ֭מַקּוּ חַבּוּרֹתָ֑י מִ֝פְּנֵ֗י אִוַּלְתִּֽי׃ | 6 | Because of how long this suffering has gone on, My wounds have become foul with rot because of my folly. |

| נַעֲוֵ֣יתִי שַׁחֹ֣תִי עַד־מְאֹ֑ד כָּל־הַ֝יּ֗וֹם קֹדֵ֥ר הִלָּֽכְתִּי׃ | 7 | I have become completely contorted because of my pain . I have walked about constantly mourning because of my suffering . |

| כִּֽי־כְ֭סָלַי מָלְא֣וּ נִקְלֶ֑ה וְאֵ֥ין מְ֝תֹ֗ם בִּבְשָׂרִֽי׃ | 8 | For my sides are full of inflammation, and there is no sound spot in my flesh. |

| נְפוּג֣וֹתִי וְנִדְכֵּ֣יתִי עַד־מְאֹ֑ד שָׁ֝אַ֗גְתִּי מִֽנַּהֲמַ֥ת לִבִּֽי׃ | 9 | I have become weak and have been crushed completely. I have been groaning because of the severe suffering of my heart because of my pain and my sin . |

| אֲֽדֹנָי נֶגְדְּךָ֥ כָל־תַּאֲוָתִ֑י וְ֝אַנְחָתִ֗י מִמְּךָ֥ לֹא־נִסְתָּֽרָה׃ | 10 | My Lord, everything I long for, especially relief from this suffering, is before you since you know the hearts of all , and my moaning is not hidden from you. Because you see what I long for and you are able to heal, you should help me. I have placed my situation and my longing before you and now I must wait for you to answer. |

| לִבִּ֣י סְ֭חַרְחַר עֲזָבַ֣נִי כֹחִ֑י וְֽאוֹר־עֵינַ֥י גַּם־הֵ֝֗ם אֵ֣ין אִתִּֽי׃ | 11 | My heart has been pounding. My strength has abandoned me, and the light of my eyes whose presence indicates life, even that is not with me, so I am close to death! |

| אֹֽהֲבַ֨י ׀ וְרֵעַ֗י מִנֶּ֣גֶד נִגְעִ֣י יַעֲמֹ֑דוּ וּ֝קְרוֹבַ֗י מֵרָחֹ֥ק עָמָֽדוּ׃ | 12 | Those who love me, my companions, are standing far away from my injury, and my relatives have stood at a distance because they see my disease as a judgment from YHWH because of my sin and want to distance themselves from that judgment. Those who are supposed to be close to me are abandoning me instead of helping and supporting me. I am alone. |

| וַיְנַקְשׁ֤וּ ׀ מְבַקְשֵׁ֬י נַפְשִׁ֗י וְדֹרְשֵׁ֣י רָ֭עָתִי דִּבְּר֣וּ הַוּוֹת | 13 | Because I am weak and my friends have abandoned me, my enemies have begun to take advantage of my weak state. And those who seek to take my life have set a trap, taking advantage of my weakness, and those who pursue my harm have been speaking of disaster, telling lies to destroy me, and they are constantly muttering treachery, covering up facts to hurt me. |

| וּ֝כְאִלֵּ֗ם לֹ֣א יִפְתַּח־פִּֽיו׃ | 14 | But I, like a deaf person, cannot hear their accusations . And [I am] like a mute person [who] cannot open his mouth. There is nothing I can do to defend myself without making the situation worse, so I have chosen to ignore them and remain silent. |

| וָאֱהִ֗י כְּ֭אִישׁ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לֹא־שֹׁמֵ֑עַ | 15 | And so I have become like a man who does not hear and so has no way of responding to the accusations and who has no arguments in his mouth. So I must rely on others to defend my case. |

| כִּֽי־לְךָ֣ יְהוָ֣ה הוֹחָ֑לְתִּי | 16 | I cannot answer my enemies myself, but I will rely on you to speak for me. That's why, YHWH, I have hoped for you because I believe you are able to help and will act . You yourself are the one who must answer the accusations of my enemies, not me , my Lord, my God. You are the only one who can help. |

| כִּֽי־אָ֭מַרְתִּי פֶּן־יִשְׂמְחוּ־לִ֑י בְּמ֥וֹט רַ֝גְלִ֗י עָלַ֥י הִגְדִּֽילוּ׃ | 17 | I have not spoken, for I thought that, even if I did, they would rejoice concerning me like they have in the past, mocking my feeble reply, [those who] have considered themselves superior to me when my feet slip, like they did when I sinned, leaving me vulnerable to attack. |

| כִּֽי־אֲ֭נִי לְצֶ֣לַע נָכ֑וֹן וּמַכְאוֹבִ֖י נֶגְדִּ֣י תָמִֽיד׃ | 18 | I have not spoken; for I am certain that I will stumble and so everyone will know I am still sick. They will think that you are still punishing me. And so I will be vulnerable to attack and any argument I make will still lead to my destruction. And my pain from my sin and discipline is always before me — yet another reason they will think you are still punishing me! |

| כִּֽי־עֲוֺנִ֥י אַגִּ֑יד אֶ֝דְאַ֗ג מֵֽחַטָּאתִֽי׃ | 19 | Although I publicly confess my iniquity, I am still distressed about what will happen because of my sin since my enemies can use it against me to support their accusations. My confession will not change my situation; I'm still suffering and so everyone thinks that I still have sin to be punished for. My sin still feels unresolved! |

| וְֽ֭אֹיְבַי *חִנָּם* עָצֵ֑מוּ וְרַבּ֖וּ שֹׂנְאַ֣י שָֽׁקֶר׃ | 20 | And those who are my enemies for no reason they hate me even though I haven't sinned against them! are mighty, but I am sick and weak. And those who hate me without cause are numerous. But I am alone and therefore defenseless so I cannot fight them. Because I haven't done anything against them and have confessed all the sin I am aware of, I don't think I have done anything to provoke these enemies. I don't deserve their hatred or their accusations! |

| וּמְשַׁלְּמֵ֣י רָ֭עָה תַּ֣חַת טוֹבָ֑ה יִ֝שְׂטְנ֗וּנִי תַּ֣חַת רָֽדְפִי־טֽוֹב׃ | 21 | And because I am vulnerable and defenseless and they consider themselves superior to me and seek my destruction, those who repay with evil in response to good falsely accuse me in response to my pursuit of good. Even though I pursue good, they still attack me! They hope to destroy me with these accusations. |

| אַל־תַּֽעַזְבֵ֥נִי יְהוָ֑ה אֱ֝לֹהַ֗י אַל־תִּרְחַ֥ק מִמֶּֽנִּי׃ | 22 | I cannot answer them myself, so do not abandon me, YHWH, unlike how my strength has abandoned me! My God, do not be far from me unlike how my friends are far from me! You are the only one left who can answer for me! |

| ח֥וּשָׁה לְעֶזְרָתִ֑י אֲ֝דֹנָ֗י תְּשׁוּעָתִֽי׃ | 23 | I need help quickly since I expect to stumble at any moment. So hurry to help me like I trust that you will, my Lord, my salvation! |

There are currently no Imagery Tables available for this psalm.

Bibliography

- Arndt, William, Frederick W. Danker, Walter Bauer, and F. Wilbur Gingrich. 2000. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1871. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms: Vol. 2. Translated by Francis Bolton. Edinburgh: T & T Clark.

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 2: 85 Psalms and Job 4–14). Vol. 2. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Gunkel, Hermann. 1926. Die Psalmen. 4th ed. Göttinger Handkommentar Zum Alten Testament 2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ________. 1998. An Introduction to the Psalms: The Genres of the Religious Lyric of Israel. Translated by James D. Nogalski. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1868. Die Psalmen. Vol. 2. Gotha: Friedrich Andreas Perthes.

- Jenni, Ernst. 1992. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 1: Die Präposition Beth. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer.

- Kim, Young Bok. 2022. Hebrew Forms of Address: A Sociolinguistic Analysis. Atlanta: SBL Press.

- Keel, Othmar. 1997. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Labuschagne, Casper J. 2008. “Psalm 38 - Logotechnical Analysis.” Numerical Features of the Psalms and Other Selected Texts. August 5, 2008.

- Leveen, J. 1971. “Textual Problems in the Psalms.” VT 21: 48–58.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2006. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter. Vol. 1 of 3 vols. Oudtestamentische Studiën 53. Leiden: Brill.

- Mowinckel, Sigmund. 1962. The Psalms in Israel’s Worship. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Rashi. Rashi on Psalms.

- Ryken, Leland, Jim Wilhoit, Tremper Longman, Colin Duriez, Douglas Penney, and Daniel G. Reid, eds. 1998. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

- Wolff, Hans Walter. 1974. Anthropology of the Old Testament. Translated by Margaret Kohl. Philadelphia: Fortress.

- Smend, Rudolf. 1888. "Ueber das Ich der Psalmen." In Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 8. Giessen: J. Ricker'sche Buchhandlung.

- Terrien, Samuel L. 2003. The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. ECC. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Footnotes

- ↑ Common-ground assumptions include information shared by the speaker and hearers. In our analysis, we mainly use this category for Biblical/ANE background - beliefs and practices that were widespread at this time and place. This is the background information necessary for understanding propositions that do not readily make sense to those who are so far removed from the culture in which the proposition was originally expressed.

- ↑ Local-ground assumptions are those propositions which are necessarily true if the text is true. They include both presuppositions and entailments. Presuppositions are those implicit propositions which are assumed to be true by an explicit proposition. Entailments are those propositions which are necessarily true if a proposition is true.

- ↑ Whereas local-ground assumptions are inferences which are necessarily true if the text is true, play-ground assumptions are those inferences which might be true if the text is true.