Psalm 46 Discourse

About the Discourse Layer

Our Discourse Layer includes four additional layers of analysis:

- Participant analysis

- Macrosyntax

- Speech act analysis

- Emotional analysis

For more information on our method of analysis, click the expandable explanation button at the beginning of each layer.

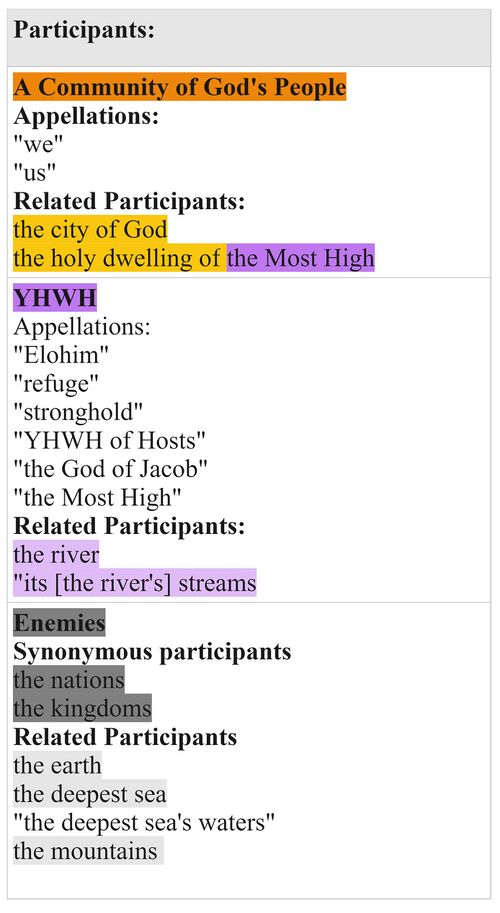

Participant Analysis

Participant Analysis focuses on the characters in the psalm and asks, “Who are the main participants (or characters) in this psalm, and what are they saying or doing? It is often helpful for understanding literary structure, speaker identification, etc.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Participant Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Participant Relations Diagram

The relationships among the participants may be abstracted and summarized as follows:

Macrosyntax

The macrosyntax layer rests on the belief that human communicators desire their addressees to receive a coherent picture of their message and will cooperatively provide clues to lead the addressee into a correct understanding. So, in the case of macrosyntax of the Psalms, the psalmist has explicitly left syntactic clues for the reader regarding the discourse structure of the entire psalm. Here we aim to account for the function of these elements, including the identification of conjunctions which either coordinate or subordinate entire clauses (as the analysis of coordinated individual phrases is carried out at the phrase-level semantics layer), vocatives, other discourse markers, direct speech, and clausal word order.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Macrosyntax Creator Guidelines.

Macrosyntax Diagram

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[1] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[2] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Speech Act Analysis

The Speech Act layer presents the text in terms of what it does, following the findings of Speech Act Theory. It builds on the recognition that there is more to communication than the exchange of propositions. Speech act analysis is particularly important when communicating cross-culturally, and lack of understanding can lead to serious misunderstandings, since the ways languages and cultures perform speech acts varies widely.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Speech Act Analysis Creator Guidelines.

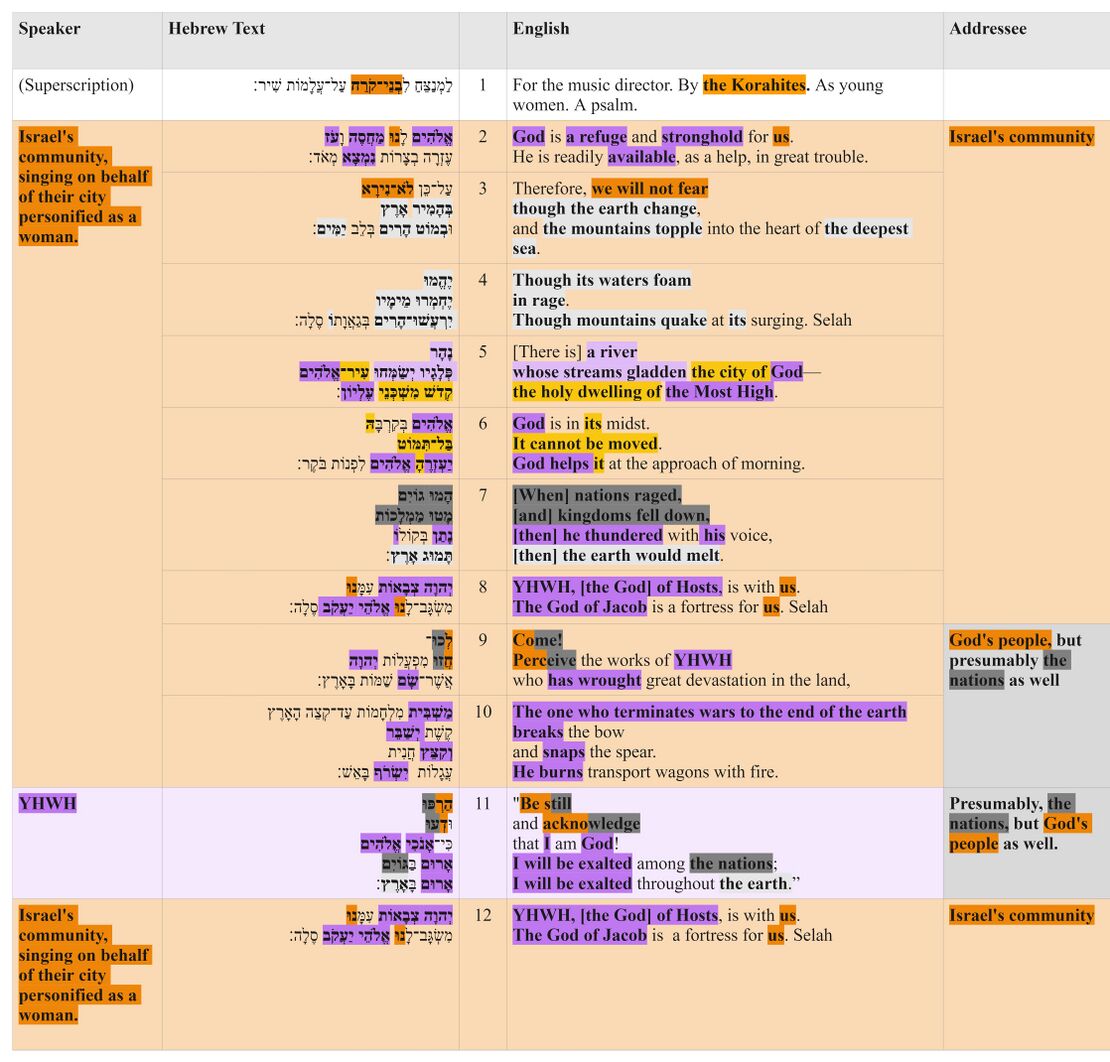

Summary Visual

Speech Act Chart

The following chart is scrollable (left/right; up/down).

| Verse | Hebrew | CBC | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) |

| Verse number and poetic line | Hebrew text | English translation | Declarative, Imperative, or Interrogative Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

Assertive, Directive, Expressive, Commissive, or Declaratory Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

More specific illocution type with paraphrased context | Illocutionary intent (i.e. communicative purpose) of larger sections of discourse These align with the "Speech Act Summary" headings |

What the speaker intends for the address to think | What the speaker intends for the address to feel | What the speaker intends for the address to do |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

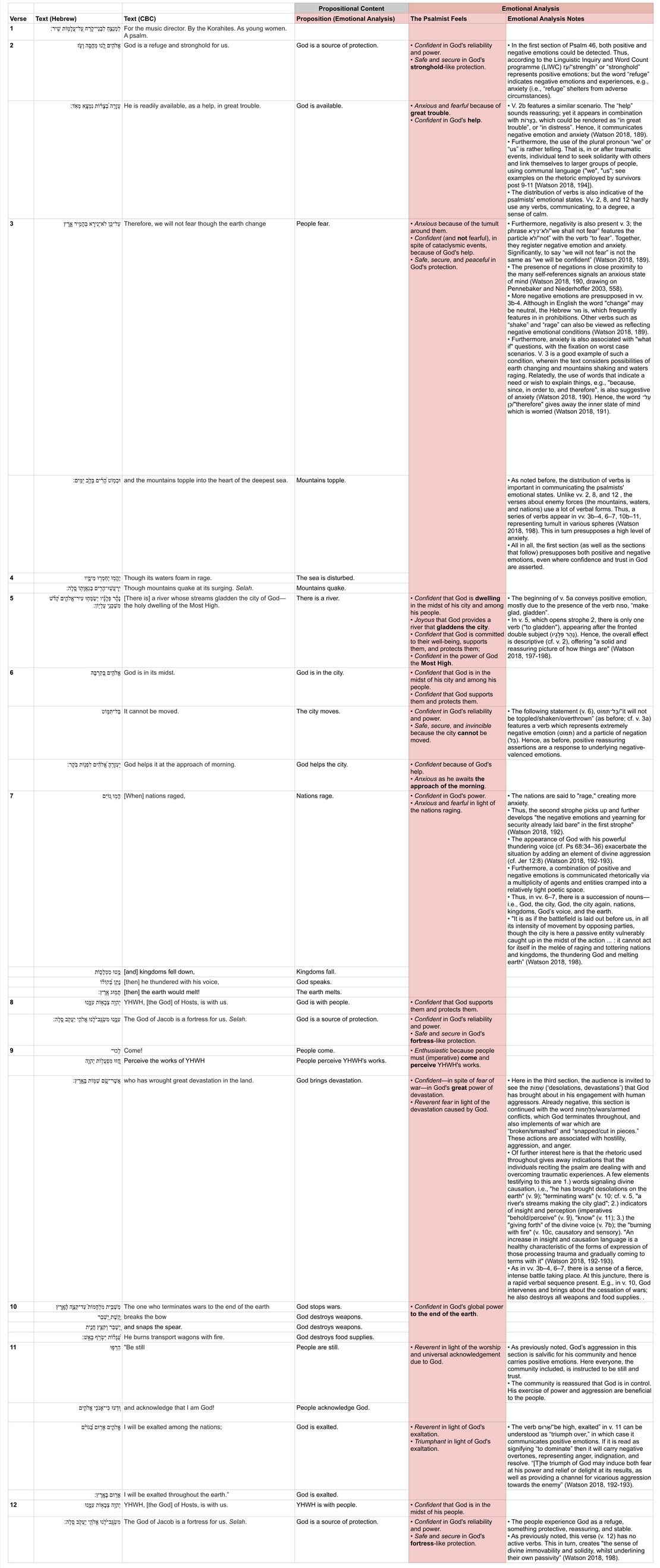

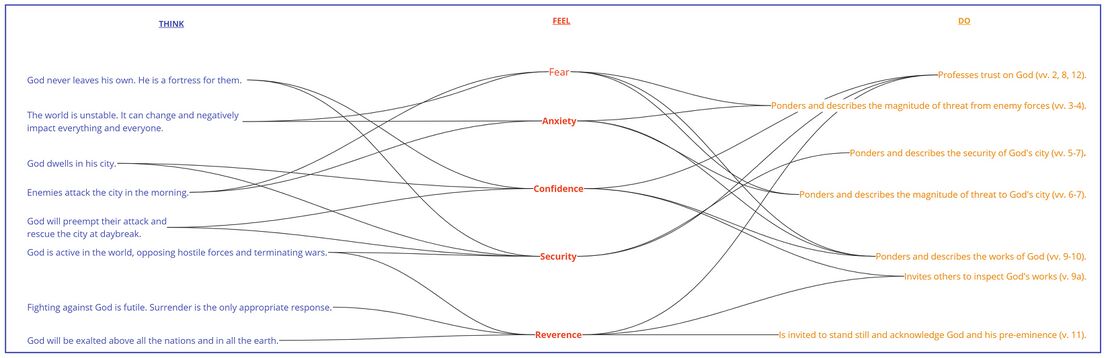

Emotional Analysis

This layer explores the emotional dimension of the biblical text and seeks to uncover the clues within the text itself that are part of the communicative intent of its author. The goal of this analysis is to chart the basic emotional tone and/or progression of the psalm.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Emotional Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Emotional Analysis Chart

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

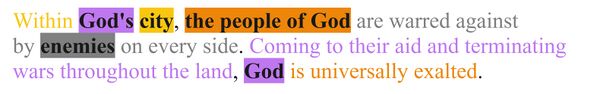

Summary Visual

Bibliography

- Abernethy, Andrew T. 2019. "‘Mountains Moved into the Sea’: The Western Reception of Psalm 46:1 and 3 [45:1 and 3 LXX] From the Septuagint to Luther." The Journal of Theological Studies 70: 523–545.

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2018. Serial Verbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, Arnold Albert. 1981. The Book of Psalms: Based on the Revised Standard Version. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Bach, Robert. 1971. “... Der Bogen zerbricht, Spiesse zerschlägt und Wagen mit Feuer verbrennt.” Pages 13–26 in Probleme biblischer Theologie. Edited by Hans Walter Wolff. Munich: Kaisere.

- Bachvarova, M. 2008. "Sumerian Gala Priests and Eastern Mediterranean Returning Gods: Tragic Lamentation in Cross-Cultural Perspective." Pages 18–52 in Lament: Studies in the Ancient Mediterranean and Beyond. Edited by Ann Suter. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Briggs, Charles Augustus and Emilie Grace Briggs. 1907. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Vol. 2. ICC. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Cornell, Collin. 2020. Divine Aggression in Psalms and Inscriptions: Vengeful Gods and Loyal Kings. SOTSM. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Craigie, Peter C., and Marvin E. Tate. 1983. Psalms 1–50. 2nd ed. WBC 19. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Creach, Jerome F.D. 1996. Yahweh as Refuge and the Editing of the Hebrew Psalter. JSOTSup 217. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Dahood, Mitchell. 1966. Psalms. Vol. 1. AB. New York: Doubleday.

- Day, P. 1995. "The Personification of Cities in the Hebrew Bible: The Thesis of Aloysius Fitsgerald, F.S.C.," Pages 283-302 in Reading From This Place: Social Location and Biblical Interpretation. Edited by Fernando Segovia and Mary Ann Tolbert. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Day, John. 1985. God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea: Echoes of a Canaanite Myth in the Old Testament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DeClaissé-Walford, Nancy, Rolf A. Jacobson, and Beth LaNeel Tanner. 2014. The Book of Psalms. NICOT. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1883. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms. vol. 1. Translated by Eaton David. New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

- Dobbs-Allsopp, F. 1993. Weep, O Daughter of Zion: A Study of the City-Lament Genre in the Hebrew Bible. Rome: Editrice Pontificio Istituto Biblico.

- Duhm, Bernhard. 1922. Die Psalmen. 2nd ed. Kurzer Hand-Commentar Zum Alten Testament 14. Tübingen: Mohn (Paul Siebeck).

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 2: 85 Psalms and Job 4–14). Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen, Drenthe: Van Gorcum.

- Futato, Mark D. 2007. Interpreting the Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel.

- Goldingay, John. 2007. Psalms 42–89. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

- Goulder, Michael D. 1982. The Psalms of the Sons of Korah. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

- Grayson. Kirk A. and Jamie Novotny. 2014. The Royal Inscriptions of Sennacherib, King of Assyria (704–681 BC). University Park, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, Eisenbrauns.

- Gunkel, Hermann. 1895. Schopfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- ________. 1968. Die Psalmen. HK II.2. Göttingen.

- Gwaltney, W. 1983. "The Biblical Book of Lamentations in the Context of Near Eastern Lament Literature." Pages 191–212 in More Essays on the Comparative Method: Scripture in Context II. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Hayes, John. 1963. “The Tradition of Zion’s Inviolability.” Journal of Biblical Literature 82, no. 4: 419-426.

- Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm. 1863. Commentary on the Psalms. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 1993. Die Psalmen I. Neue Echter Bibel. Würzburg: Echter.

- Jenni, Ernst. 2012. "Nif’al und Hitpa‘el im Biblisch-Hebräischen." Pages 131-304 in Studien zur Sprachwelt des Alten Testaments III. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Jacobson, Rolf. A. 2020. "Psalm 46: Translation, Structure, and Theology." Word and World 40: 308-320.

- Junker, H. 1962. "Der Strom, dessen Arme die Stadt Gottes erfreuen (Ps. 46,5)." Biblica 43: 197-201.

- Keel, Othmar. 1997. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Translated by T.J. Hallett. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Kissane, Edward. 1953. The Book of Psalms. Vol. 1. Westminster, MD: The Newman Press.

- Klingbeil, Martin. 1999. Yahweh Fighting from Heaven. God as Warrior and as God of Heaven in the Hebrew Psalter and Ancient Near Eastern Iconography. OBO 169. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Kolyada, Yelena. 2009. A Compendium of Musical Instruments and Instrumental Terminology in the Bible. Bible World. London: Equinox.

- Kraus, Hans-Joachim. 1972. Psalmen 1–63. BKT XV/1. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag.

- Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count Program: http://www.liwc.net/

- Loretz, Oswald. 1979. Die Psalmen: Beitrag der Ugarit-Texte zum Verständnis von Kolometrie und Textologie der Psalmen. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag.

- L., S.H. 1916. "An Ancient Babylonian Map." The Museum Journal VII, 4: 263-268. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.penn.museum/sites/journal/530/

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2010. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry. Vol. 2. Oudtestamentische Studiën 53. Leiden: Brill.

- Lunn, Nicholas P. 2006. Word Order Variation in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: The Role of Pragmatics and Poetics in the Verbal Clause. Paternoster Biblical Monographs. Milton Keynes: Paternoster.

- Maier, Christl. 2008. Daughter Zion, Mother Zion: Gender, Space, and the Sacred in Ancient Israel. Minneapolis, MI: Fortress Press.

- Mena, Andrea K. 2012. The Semantic Potential of in Genesis, Psalms, and Chronicles. MA thesis, Stellenbosch University.

- Miller, P.D. 1973. The Divine Warrior in Early Israel. HSM 5. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Miller, Robert D. 2010. “The Zion Hymns as Instruments of Power.” Ancient Near Eastern Studies 47: 217–39.

- ________. 2018. The Dragon, the Mountain, and the Nations: An Old Testament Myth, Its Origins, and Its Afterlives. Explorations in Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Neve, Lloyd. 1974/75. "The Common Use of Traditions by the Author of Psalm 46 and Isaiah." The Expository Times 86: 243-246.

- O’Kelly, Matthew A. 2024. "Stillness and Salvation: Reading Psalm 46 in Its Context." Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 48: 371–383.

- Peterson, Eugene H. 2003. The Message. Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

- Raabe, P.R. 1990. Psalm Structures. A Study of Psalms with Refrains. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 104. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

- RINAP: Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period (RINAP) Project

- Quine, Cat. 2020. Casting Down the Host of Heaven: The Rhetoric of Ritual Failure in the Polemic Against the Host of Heaven. Old Testament Studies 78. Leiden: Brill.

- Sawyer, John F.A. 2011. “The Terminology of the Psalm Headings.” Pages 288-298 in Sacred Text and Sacred Meanings: Studies in Biblical Language and Literature. Collected Essays by John F.A. Sawyer. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix.

- Schroer, Sylvia. 2008. "Gender and Iconography from the Viewpoint of a Feminist Biblical Scholar." Lectio Deficilio 2: 1-25.

- Trimm, Charlie. 2017. Fighting for the King and the Gods: A Survey of Warfare in the Ancient Near East. Resources for Biblical Studies 88. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature Press.

- Tsumura, David Toshio. 1980. “The Literary Structure of Psalm 46, 2-8.” Annual of the Japanese Biblical Institute 6: 29-55.

- ________. 1981. "Twofold Image of Wine in Psalm 46:4-5." Jewish Quarterly Review 71: 167-175.

- ________. 2014. Creation and Destruction: A Reappraisal of the Chaoskampf Theory in the Old Testament. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Waltke, Bruce K., James M. Houston and Erika Moore. The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2010.

- Watson, Rebecca S. 2005. Chaos Uncreated: A Reassessment of the Theme of “Chaos” in the Hebrew Bible. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 341. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ________. 2018. “'Therefore We Will Not Fear”? The Psalms of Zion in Psychological Perspective." Pages 182-216 in The City in the Hebrew Bible: Critical, Literary and Exegetical Approaches. Edited by James K. Aitken and Hilary F. Marlow. LHBOTS 672. London: T&T Clark.

- Weber, B. 2001 and 2003. Werkbuch Psalmen. 2 vols. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Weiser, Artur. 1962. The Psalms. OTL. Translated by Herbert Hartwell. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press.

- Welton, Rebekah. 2024. "Yahweh the Wrathful Vintner: Blood and Wine-making Metaphors in Isaiah 49:26a and 63:6." Journal for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies 4: 19-41.

- Wilson, Gerald. 2002. Psalms. Vol. 1. NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Wright, Jacob. 2015. “Urbicide: The Ritualized Killing of Cities in the Ancient Near East.” Pages 147-166 in Ritual Violence in the Hebrew Bible: New Perspective. Edited by Saul M. Olyan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ziegler, Joseph. 1950. “Die Hilfe Gottes ‘am Morgen.’” Pages 281–88 in Alttestamentliche Studien. Edited by Hubert Junker and Johannes Botterweck. Bonn: Hanstein.

Footnotes

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.