Psalm 110 Discourse

About the Discourse Layer

Our Discourse Layer includes four additional layers of analysis:

- Participant analysis

- Macrosyntax

- Speech act analysis

- Emotional analysis

For more information on our method of analysis, click the expandable explanation button at the beginning of each layer.

Participant Analysis

Participant Analysis focuses on the characters in the psalm and asks, “Who are the main participants (or characters) in this psalm, and what are they saying or doing? It is often helpful for understanding literary structure, speaker identification, etc.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Participant Analysis Creator Guidelines.

There are six participants/characters in Psalm 110:

Profile List

| David/Psalmist |

| YHWH |

| "The Lord" (v. 5) |

| King |

| "lord" (v. 1) |

| "priest" (v. 4) |

| King's people |

| "young men" (v. 3) |

| "dew" (v. 3) |

| Wicked |

| "[Rebellious] kings" (v. 5) |

| "Head [of the rebellious kings]" (v. 6) |

| Nations |

Profile Notes

- King: The oracle begins with YHWH speaking to a person whom David calls “my lord.” This person is a king who rules alongside YHWH over the entire earth. David addresses this king as his superior: a king greater than he is, because he will see the fulfillment of the eternal and universal promises that YHWH has made. This superior will be greater not only in the extent of his kingdom, but also in his relationship to YHWH: he will be both priest and king, having immediate, special access to YHWH, and he will be successful because YHWH, himself, will do battle against his enemies.

- King's people: The king's people will be willing to serve in his army. In the ancient world, extending a kingdom happened when armies fought over territory. Professional, full-time soldiers were not common in the ancient world, so kings depended largely on volunteers to serve in their armies. It was not easy for kings to find volunteers to serve in their army. It is not difficult for this king, however. His people, i.e., his potential army, will be willing to serve in his army as soon as he announces his plans for war. He would start his campaign in the holy mountains which surround Jerusalem, and these mountains will be covered with young soldiers in the same way the grass is covered with dew in the early morning.

- Enemies: Although the king's enemies are never explicitly identified in this psalm, their fate is clearly stated: YHWH will destroy them. Moreover, the imagery of enemies as a footstool (v. 1) was also used to express both authority and victory over enemies. In other words, Psalm 110 depicts YHWH bringing victory, and then authority, over all the king’s enemies. In David's vision, YHWH smashed the heads of the rebellious kings across the wide world, and so he has extended David's lord's scepter from Zion and made his enemies a footstool for his feet. The king rules alongside YHWH over the entire earth.

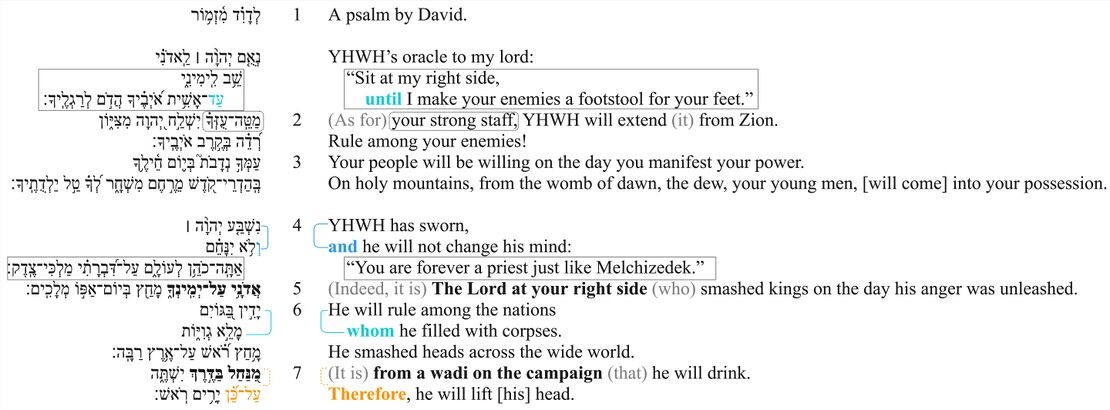

| Text (Hebrew) | Verse | Text (CBC) The Close-but-clear translation (CBC) exists to provide a window into the Hebrew text according to how we understand its syntax and word-to-phrase-level semantics. It is designed to be "close" to the Hebrew, while still being "clear." Specifically, the CBC encapsulates and reflects the following layers of analysis: grammar, lexical semantics, phrase-level semantics, and verbal semantics. It does not reflect our analysis of the discourse or of poetics. It is not intended to be used as a stand-alone translation or base text, but as a supplement to Layer-by-Layer materials to help users make full use of these resources. |

|---|---|---|

לְדָוִ֗ד מִ֫זְמ֥וֹר

|

1a | A psalm by David.

|

נְאֻ֤ם יְהוָ֨ה ׀ לַֽאדֹנִ֗י

|

1b | YHWH’s oracle to my lord:

|

שֵׁ֥ב לִֽימִינִ֑י

|

1c | “Sit at my right side,

|

עַד־אָשִׁ֥ית אֹ֝יְבֶ֗יךָ הֲדֹ֣ם לְרַגְלֶֽיךָ׃

|

1d | until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.”

|

מַטֵּֽה־עֻזְּךָ֗ יִשְׁלַ֣ח יְ֭הוָה מִצִּיּ֑וֹן

|

2a | YHWH will extend your strong staff from Zion.

|

רְ֝דֵ֗ה בְּקֶ֣רֶב אֹיְבֶֽיךָ׃

|

2b | Rule among your enemies!

|

עַמְּ ךָ֣ נְדָבֹת֮ בְּ י֪וֹם חֵ֫ילֶ֥ ךָ

|

3a | Your people will be willing on the day you manifest your power.

|

בְּֽהַדְרֵי־קֹ֭דֶשׁ מֵרֶ֣חֶם מִשְׁחָ֑ר

|

3b | On holy mountains, from the womb of dawn,

|

לְ֝ ךָ֗ טַ֣ל יַלְדֻתֶֽי ךָ׃

|

3c | The dew, your young men, [will come] into your possession.

|

נִשְׁבַּ֤ע יְהוָ֨ה ׀ וְלֹ֥א יִנָּחֵ֗ם

|

4a | YHWH has sworn, and he will not change his mind:

|

אַתָּֽה־כֹהֵ֥ן לְעוֹלָ֑ם

|

4b | “You are forever a priest

|

עַל־דִּ֝בְרָתִ֗י מַלְכִּי־צֶֽדֶק׃

|

4c | just like Melchizedek.”

|

אֲדֹנָ֥י עַל־יְמִֽינְךָ֑

|

5a | The Lord at your right side

|

מָחַ֖ץ בְּ יוֹם־ אַפּ֣ וֹ מְלָכִֽים׃

|

5b | smashed kings on the day his anger was unleashed.

|

יָדִ֣ין בַּ֭גּוֹיִם מָלֵ֣א גְוִיּ֑וֹת

|

6a | He will rule among the nations whom he filled with corpses.

|

מָ֥חַץ רֹ֝֗אשׁ עַל־אֶ֥רֶץ רַבָּֽה׃

|

6b | He smashed heads across the wide world.

|

מִ֭נַּחַל בַּדֶּ֣רֶךְ יִשְׁתֶּ֑ה

|

7a | He will drink from a wadi on the campaign.

|

עַל־כֵּ֝֗ן יָרִ֥ים רֹֽאשׁ׃

|

7b | Therefore, he will lift [his] head.

|

Notes

- The speakers of the psalm: Although YHWH speaks directly in v. 1aβ-b and v. 4b-c, there is a sense in which YHWH is speaking throughout the psalm, through the voice of his prophet David. As Hilber notes, "the whole of Psalm 110 has integrity as a unified prophetic oracle, and the components of the psalm should not be differentiated in terms of Yahweh's words in distinction from the prophet's words."[1]

- The addressee of the psalm: The king, whom the speaker addresses in the second person (vv. 1aβb, 2, 3, 4bc, 5), is the addressee throughout the psalm. The third person אדני ("my lord") in v. 1aα does not imply that the king is not the addressee at this point in the psalm, because a speaker will often use third person language when speaking to an addressee if the addressee is a superior in some sense (see e.g., Jacob's encounter with Esau in Gen. 33:8-14; cf. 1 Sam. 26:19).

- The subjects in vv. 5-7: For a thorough discussion of this issue, see The Subject(s) in Psalm 110:5-7. In short, YHWH is probably the subject in v. 7 for the following reasons:

- (1) אֲדֹנָי ("the Lord" = YHWH) is named as the subject in v. 5a, and "there is no indication in the sequence of clauses in vv. 5-7 that we should assume a change of subject."[2]

- (2) The act of drinking from a stream naturally follows the act of smashing heads (e.g., Judges 15:15-19). Thus, the subject of vv. 5-6 (the warrior who smashes heads) is most likely also the subject of v. 7 (the one who drinks to quench his thirst).[3]

- (3) Throughout the psalm, the king is the addressee and is thus referred to in the second person. The verbs in v. 7, however, are in the third person.

- Together, these reasons make it probable that YHWH is the subject of the verbs in v. 7. The number one objection scholars raise to this view is that "it is difficult to think of God as drinking from the torrent;"[4] "the action of drinking from 'a stream upon the way' is more readily comprehensible of a human king than of YHWH himself'.[5] This objection is hardly persuasive, however, because the Old Testament often describes YHWH in stark anthropomorphic terms. The motif of YHWH as a warrior is especially common (cf. Ex. 15:3). The image of YHWH as a warrior drinking from a stream in Ps. 110:7 is hardly more difficult to imagine that the image of YHWH waking "from sleep, as a warrior wakes from the stupor of wine" (Ps. 78:65).

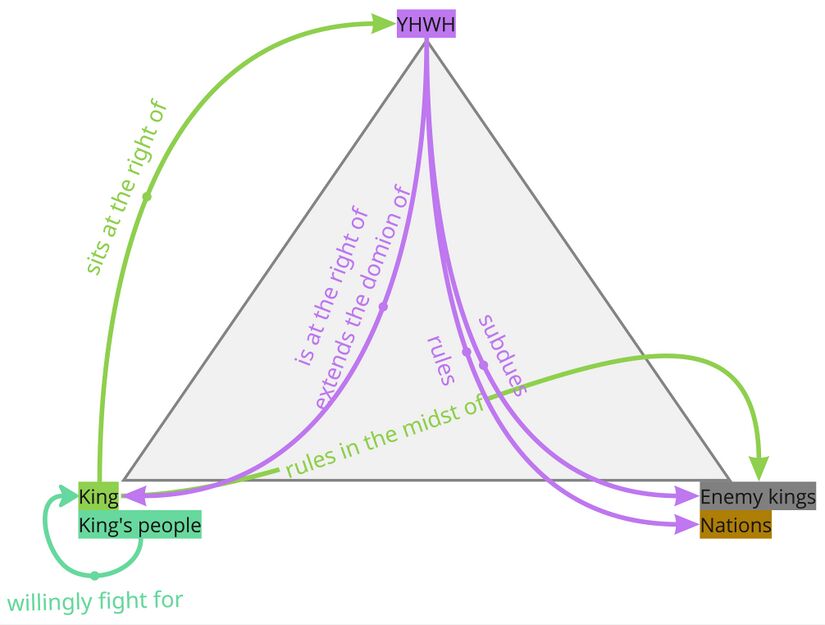

Participant Relations Diagram

The relationships among the participants may be abstracted and summarized as follows:

Macrosyntax

Macrosyntax Diagram

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[6] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[7] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Paragraph Divisions

The psalm divides into two paragraphs, and each paragraph follows a similar pattern:

- (1) introduction of direct speech (v. 1a // v. 4a)

- (2) direct speech (v. 1b // v. 4b)

- (3) fronted topic (v. 2a // v. 5)

Word Order

- v. 2. The direct object "your strong staff" (מַטֵּה־עֻזְּךָ) is fronted, probably to signal the activation of this entity as the topic of the sentence, in contrast to the "footstool" (also a royal symbol) mentioned at the end of the previous clause: "...until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet. (Now, enough with the footstool; let's talk about another royal symbol.) As for your strong staff, YHWH will extend it from Zion."[8]

- v. 3. The word order is chiastic (Subj-Pred-Adjunct // Adjunct-Pred-Subj) such that v. 3 is bound together as a poetic unit (a verse).

- v. 5. "The Lord at your right side" (אֲדֹנָ֥י עַל־יְמִֽינְךָ֑) is fronted, probably for confirming focus. In v. 1, YHWH said that he was going to subdue the king's enemies. Now, in v. 5, YHWH's role in this action is confirmed: "(Yes), it's the Lord (the one at your right hand) who smashed kings..." This fits well with the overall mood and purpose of the psalm, which is to assure the king that YHWH is going to take care of his enemies for him. Another argument for this view would be the close correspondence between Ps. 110 and Ps. 108—both are לדוד Pss. which mention YHWH’s “right hand” and subduing enemies—which ends in two clauses with clear constituent focus: בֵּֽאלֹהִ֥ים נַעֲשֶׂה־חָ֑יִל וְ֝ה֗וּא יָב֥וּס צָרֵֽינוּ. God is the one who is going to subdue our enemies.

- v. 5b. The post-verbal constituent ביום אפו is fronted before the direct object (מְלָכִים).

- v. 7a. The two prepositional phrases in v. 7a ("from a wadi on the campaign") are fronted and probably pragmatically marked.[9] The fact that the warrior takes a drink of water is not, in an of itself, noteworthy—quenching thirst after battle is assumed (cf. Judges 15:16ff). What is significant is that he takes a drink from a wadi on the campaign (i.e., from water in enemy territory), which signifies the completion of his victory.[10]

Vocatives

There are no vocatives in this psalm.

There are no Discourse Marker notes for this psalm.

Conjunctions

- v. 1b. עַד is here a subordinating conjunction, and it connects two events: (1) "the lord sitting at YHWH's right hand; (2) "YHWH making the lord's enemies a footstool for his feet." The precise temporal relationship between these two events is not immediately clear. Specifically, does the "sitting at YHWH's right hand" cease once all of the lord's enemies have been subdued, or does it continue? The Hebrew conjunction עַד, like the English conjunction "until," often implies cessation of activity in the main (non-subordinated) clause. So, for example, Gen. 38:11 says, “Remain (שְׁבִי) a widow in your father’s house, till (עַד) Shelah my son grows up (יִגְדַּל)” (and then you won't be a widow any more) (Gen. 38:11 ESV). If this applies to Ps. 110, then the sitting of the "lord" will only last until the lord's enemies have been made his footstool; then, he will cease to sit. It's possible that this understanding underlies what Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15:24-25, 28 — εἶτα τὸ τέλος, ὅταν παραδιδῷ τὴν βασιλείαν τῷ θεῷ καὶ πατρί... δεῖ γὰρ αὐτὸν βασιλεύειν ἄχρι οὗ θῇ πάντας τοὺς ἐχθροὺς ὑπὸ τοὺς πόδας αὐτοῦ... ὅταν δὲ ὑποταγῇ αὐτῷ τὰ πάντα, τότε [καὶ] αὐτὸς ὁ υἱὸς ὑποταγήσεται τῷ ὑποτάξαντι αὐτῷ τὰ πάντα, ἵνα ᾖ ὁ θεὸς [τὰ] πάντα ἐν πᾶσιν (UBS-5th.) Sometimes, however, עַד (or עַד אֲשֶׁר) "sometimes express a limit which is not absolute (terminating in the preceding action), but only relative, beyond which the action or state described in the principal clause still continues."[11] For example, Ps. 112:8 says, "His heart is steady; he will not be afraid, until (עַד אֲשֶׁר) he looks in triumph (יִרְאֶה) on his adversaries" (ESV).[12] Similarly, in Greek, the conjunction ἕως, which the LXX uses in Ps. 110:1, can mean either "until," "so long as," or, if the actions are coextensive, "while."[13]

- v. 7b. על כן functions to "Explain the grounds of why something... will happen"[14] In Ps. 110:7, the על כן clause explains the grounds of why YHWH "will lift (his) head": He will lift up his head (a gesture of victory over enemies and a sign of renewed confidence) because he is refreshed from his drink and confident that his victory is complete. See notes on Story Behind.

Speech Act Analysis

The Speech Act layer presents the text in terms of what it does, following the findings of Speech Act Theory. It builds on the recognition that there is more to communication than the exchange of propositions. Speech act analysis is particularly important when communicating cross-culturally, and lack of understanding can lead to serious misunderstandings, since the ways languages and cultures perform speech acts varies widely.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Speech Act Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Speech Act Analysis Chart

The following chart is scrollable (left/right; up/down).

| Verse | Hebrew | CBC | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) |

| Verse number and poetic line | Hebrew text | English translation | Declarative, Imperative, or Interrogative Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

Assertive, Directive, Expressive, Commissive, or Declaratory Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

More specific illocution type with paraphrased context | Illocutionary intent (i.e. communicative purpose) of larger sections of discourse These align with the "Speech Act Summary" headings |

What the speaker intends for the address to think | What the speaker intends for the address to feel | What the speaker intends for the address to do |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| Verse | Text (Hebrew) | Text (CBC) The Close-but-clear translation (CBC) exists to provide a window into the Hebrew text according to how we understand its syntax and word-to-phrase-level semantics. It is designed to be "close" to the Hebrew, while still being "clear." Specifically, the CBC encapsulates and reflects the following layers of analysis: grammar, lexical semantics, phrase-level semantics, and verbal semantics. It does not reflect our analysis of the discourse or of poetics. It is not intended to be used as a stand-alone translation or base text, but as a supplement to Layer-by-Layer materials to help users make full use of these resources. | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) | Speech Act Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | לְדָוִ֗ד מִ֫זְמ֥וֹר | A psalm by David. | Superscription | ||||||||

| 1aα | נְאֻ֤ם יְהוָ֨ה ׀ לַֽאדֹנִ֗י | YHWH’s oracle to my lord: | Fragment | Assertive | Introducing YHWH's oracle to the king. | Reporting YHWH's oracle to the king. | To assure the king of his certain success. | The future Davidic king will see that YHWH promises to give him universal dominion | The future Davidic king will feel confident in YHWH. | The future Davidic king will trust YHWH's promises. | |

| 1aβ | שֵׁ֥ב לִֽימִינִ֑י | “Sit at my right side, | Imperative •"Imperative" |

Directive • "Directive" |

"Inviting the king to sit at his right side and promising to subdue the king's enemies. • "Inviting and promising" |

||||||

| 1b | עַד־אָשִׁ֥ית אֹ֝יְבֶ֗יךָ הֲדֹ֣ם לְרַגְלֶֽיךָ׃ | until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.” | |||||||||

| 2a | מַטֵּֽה־עֻזְּךָ֗ יִשְׁלַ֣ח יְ֭הוָה מִצִּיּ֑וֹן | YHWH will extend your strong staff from Zion. | Declarative | Assertive | Assuring the king that YHWH will extend his dominion. | Assuring the king that his future success is certain. | |||||

| 2b | רְ֝דֵ֗ה בְּקֶ֣רֶב אֹיְבֶֽיךָ׃ | Rule among your enemies! | Imperative | Assertive | Assuring the king that he will rule among his enemies. | Indirect speech act: The imperative is used here (v. 2b), not as a command, but to "to express a distinct assurance... or promise, e.g., ... Ps. 110:2" (GKC 110c; cf. JM114p; IBHS 34.4c). Thus, some translations have a future here (e.g., CEV: "and you will rule over your enemies; cf. Theodotion: κατακυριεύσεις). | |||||

| 3a | עַמְּךָ֣ נְדָבֹת֮ בְּי֪וֹם חֵ֫ילֶ֥ךָ | Your people will be willing on the day you manifest your power. | Declarative | Assertive | Assuring the king that he will have a willing army. | ||||||

| 3b | בְּֽהַדְרֵי־קֹ֭דֶשׁ מֵרֶ֣חֶם מִשְׁחָ֑ר | On holy mountains, from the womb of dawn, | Declarative | Assertive | Comparing the king's army to dew. | ||||||

| 3c | לְ֝ךָ֗ טַ֣ל יַלְדֻתֶֽיךָ׃ | The dew, your young men, [will come] into your possession. | |||||||||

| 4a | נִשְׁבַּ֤ע יְהוָ֨ה ׀ וְלֹ֥א יִנָּחֵ֗ם | YHWH has sworn, and he will not change his mind: | Declarative | Assertive | Introducing YHWH's oath to the king. | Reporting YHWH's oath to the king. | |||||

| 4b | אַתָּֽה־כֹהֵ֥ן לְעוֹלָ֑ם | “You are forever a priest | Declarative • "Declarative" |

Commissive • "Commissive" |

Swearing that the king will remain a priest forever and thus committing himself to ensuring that the kings remains a priest forever. • "Swearing" |

||||||

| 4c | עַל־דִּ֝בְרָתִ֗י מַלְכִּי־צֶֽדֶק׃ | just like Melchizedek.” | Indirect speech act: In the context of an oath (שבע), the declarative statement "you are forever a priest" (v. 4) implies the speaker's commitment to maintaining the truth of that statement ("you are a priest forever" = "I will do everything in my power to ensure that you continue forever as a priest; I will never reject you"). See, for example, the many oaths in which the commitment of the one swearing is explicit (e.g., Gen 21:23-24; 22:16-18; 26:3; 47:30-31; Ps 89:4-5; 119:106; 132:11; etc). First Kgs. 1 gives a good example of an oath in which, although the sentence type is declarative, the speaker is committing to some action: '[Bathsheba] said to [David], “My lord, you yourself swore to me your servant by the Lord your God: ‘Solomon your son shall be king after me, and he will sit on my throne.' But now Adonijah has become king..." ... The king then took an oath: “As surely as the Lord lives, who has delivered me out of every trouble, I will surely carry out this very day what I swore to you by the Lord, the God of Israel: Solomon your son shall be king after me, and he will sit on my throne in my place”' (1 Kgs 1:17-18, 29-30 NIV). | ||||||||

| 5a | אֲדֹנָ֥י עַל־יְמִֽינְךָ֑ | The Lord at your right side | Declarative | Assertive | Reporting that (in his vision) YHWH smashed kings. | Reporting to the king what he saw in his prophetic vision. | |||||

| 5b | מָחַ֖ץ בְּיוֹם־אַפּ֣וֹ מְלָכִֽים׃ | smashed kings on the day his anger was unleashed. | |||||||||

| 6a | יָדִ֣ין בַּ֭גּוֹיִם מָלֵ֣א גְוִיּ֑וֹת | He will rule among the nations whom he filled with corpses. | Declarative | Assertive | Predicting that YHWH (having smashed kings) will rule the nations. | ||||||

| 6b | מָ֥חַץ רֹ֝֗אשׁ עַל־אֶ֥רֶץ רַבָּֽה׃ | He smashed heads across the wide world. | Declarative | Assertive | Reporting that (in his vision) YHWH smashed heads. | ||||||

| 7a | מִ֭נַּחַל בַּדֶּ֣רֶךְ יִשְׁתֶּ֑ה | He will drink from a wadi on the campaign. | Declarative | Assertive | Predicting that YHWH (having smashed heads) will drink from a wadi on the campaign. | ||||||

| 7b | עַל־כֵּ֝֗ן יָרִ֥ים רֹֽאשׁ׃ | Therefore, he will lift [his] head. | Declarative | Assertive | Predicting that YHWH will lift his head. | ||||||

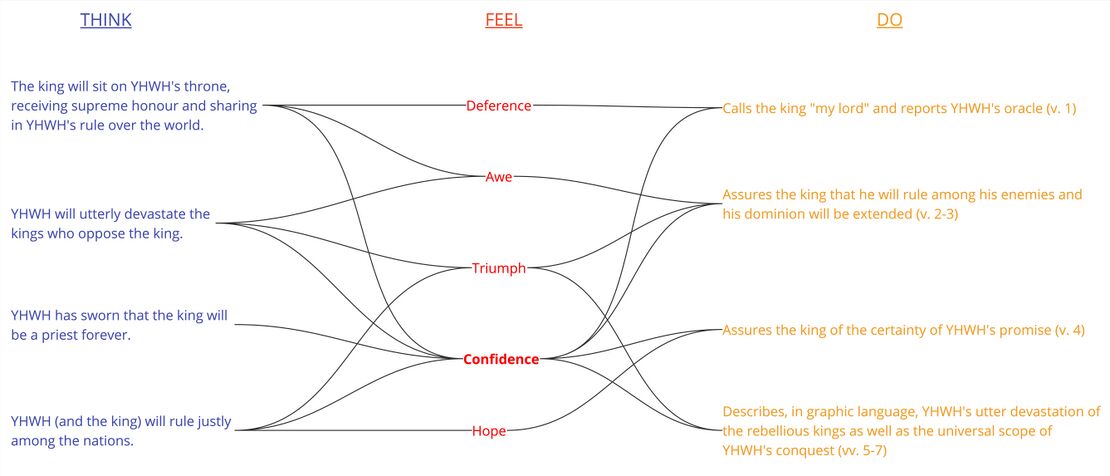

Emotional Analysis

This layer explores the emotional dimension of the biblical text and seeks to uncover the clues within the text itself that are part of the communicative intent of its author. The goal of this analysis is to chart the basic emotional tone and/or progression of the psalm.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Emotional Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Emotional Analysis Chart

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| Verse | Text (Hebrew) | Text (CBC) The Close-but-clear translation (CBC) exists to provide a window into the Hebrew text according to how we understand its syntax and word-to-phrase-level semantics. It is designed to be "close" to the Hebrew, while still being "clear." Specifically, the CBC encapsulates and reflects the following layers of analysis: grammar, lexical semantics, phrase-level semantics, and verbal semantics. It does not reflect our analysis of the discourse or of poetics. It is not intended to be used as a stand-alone translation or base text, but as a supplement to Layer-by-Layer materials to help users make full use of these resources. | The Psalmist Feels | Emotional Analysis Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | לְדָוִ֗ד מִ֫זְמ֥וֹר | A psalm by David. | ||

| 1aα | נְאֻ֤ם יְהוָ֨ה ׀ לַֽאדֹנִ֗י | YHWH’s oracle to my lord: | • Deference to his lord. • Confident that his lord's enemies will be utterly and permanently subdued (as a footstool for his feet). |

|

| 1aβ | שֵׁ֥ב לִֽימִינִ֑י | “Sit at my right side, | ||

| 1b | עַד־אָשִׁ֥ית אֹ֝יְבֶ֗יךָ הֲדֹ֣ם לְרַגְלֶֽיךָ׃ | until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.” | ||

| 2a | מַטֵּֽה־עֻזְּךָ֗ יִשְׁלַ֣ח יְ֭הוָה מִצִּיּ֑וֹן | YHWH will extend your strong staff from Zion. | • Impressed/Admiration at the strength of his lord's staff (> dominion). • Confident and excited that his lord will rule(!) among his enemies. • Triumph, because his lord will rule among his enemies. |

• The imperative is used here, not as a command, but to "to express a distinct assurance... or promise, e.g., ... Ps. 110:2" (GKC 110c). • See story behind notes for the "staff" image.

|

| 2b | רְ֝דֵ֗ה בְּקֶ֣רֶב אֹיְבֶֽיךָ׃ | Rule among your enemies! | ||

| 3a | עַמְּךָ֣ נְדָבֹת֮ בְּי֪וֹם חֵ֫ילֶ֥ךָ | Your people will be willing on the day you manifest your power. | • Impressed/Admiration at the quality and quantity of his lord's army, which is like dew. • Determined to celebrate his lord's military might. |

• See story behind imagery chart on "dew."

|

| 3b | בְּֽהַדְרֵי־קֹ֭דֶשׁ מֵרֶ֣חֶם מִשְׁחָ֑ר | On holy mountains, from the womb of dawn, | ||

| 3c | לְ֝ךָ֗ טַ֣ל יַלְדֻתֶֽיךָ׃ | The dew, your young men, [will come] into your possession. | ||

| 4a | נִשְׁבַּ֤ע יְהוָ֨ה ׀ וְלֹ֥א יִנָּחֵ֗ם | YHWH has sworn, and he will not change his mind: | • Confident that YHWH will not change his mind, and, therefore, confident that his lord will be a priest forever. |

|

| 4b | אַתָּֽה־כֹהֵ֥ן לְעוֹלָ֑ם | “You are forever a priest | ||

| 4c | עַל־דִּ֝בְרָתִ֗י מַלְכִּי־צֶֽדֶק׃ | just like Melchizedek.” | ||

| 5a | אֲדֹנָ֥י עַל־יְמִֽינְךָ֑ | The Lord at your right side • Contempt for the foolish rebellious kings whom YHWH will smash on the day his anger is unleashed, so that they become corpses. • Confident that the kings will be utterly devastated on that day. • Triumph at their defeat at the hands of the Lord, who smashed heads across the wide world and filled the nations with corpses. • Hopeful that the world will be ruled with justice when YHWH becomes king. |

• The verb מחץ, which appears only in poetic texts, has very strong associations with violence and gore (cf. "corpses" in v. 6a). Smashing "heads" of enemies especially common (Hab. 3:13; Pss. 68:22; 110:6; cf. Num. 24:17; Jdg. 5:26). The psalmist may have used such graphic language, in part, to express his contempt for the kings and his confidence that they will be utterly devastated. • In vv. 5-6, the psalmist is probably reporting what he saw in his vision (see notes on verbal semantics). The fact that the psalmist saw these things take place in his dream may contribute to his confidence that they will take place in reality. • YHWH is referred to as "the Lord," a designation which underscores "the universal authority of God"(NIDOTTE) (cf. Ps. 2:4b).

| |

| 5b | מָחַ֖ץ בְּיוֹם־אַפּ֣וֹ מְלָכִֽים׃ | smashed kings on the day his anger was unleashed. | ||

| 6a | יָדִ֣ין בַּ֭גּוֹיִם מָלֵ֣א גְוִיּ֑וֹת | He will rule among the nations whom he filled with corpses. | ||

| 6b | מָ֥חַץ רֹ֝֗אשׁ עַל־אֶ֥רֶץ רַבָּֽה׃ | He smashed heads across the wide world. | ||

| 7a | מִ֭נַּחַל בַּדֶּ֣רֶךְ יִשְׁתֶּ֑ה | He will drink from a wadi on the campaign. | • For the images of drinking from a wadi on the campaign and lifting one's head, see notes on story behind.

| |

| 7b | עַל־כֵּ֝֗ן יָרִ֥ים רֹֽאשׁ׃ | Therefore, he will lift [his] head. | • Confidence that YHWH's victory will be complete. • Triumph in the victory of YHWH and the lord. |

Bibliography

- Alan KamYau, Chan. 2016. ”7 A Literary and Discourse Analysis of Psalm 110.” In Melchizedek Passages in the Bible: A Case Study for Inner-Biblical and Inter-Biblical Interpretation, 97-118. Warsaw, Poland: De Gruyter Open Poland.

- Alter, Robert. 2011. The Art of Biblical Poetry. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Barbiero, Gianni. 2014. "The non-violent messiah of Psalm 110". Biblische Zeitschrift 58, 1: 1-20.

- Barthélemy, Dominique. 2005. Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament. Vol. Tome 4: Psaumes. Fribourg, Switzerland: Academic Press.

- Booij, Thijs. 1991. "Psalm Cx: Rule in the Midst of Your Foes!" Vetus Testamentum. Vol. 41, no.: 396-407.

- Bratcher, Robert G. and William David Reyburn. 1991. A Translator’s Handbook on the Book of Psalms. UBS Handbook Series. New York: United Bible Societies.

- Briggs, Charles and Emilie Briggs. 1907. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. International Critical Commentary. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.

- Caquot, André. 1956. "Remarques sur le Psaume CX." Semitica. Vol. 6: 33-52.

- de Hoop, Raymond, and Paul Sanders. 2022. “The System of Masoretic Accentuation: Some Introductory Issues”. The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 22.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1877. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms: Vol. 3. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Driver, G. R. 1964. "Psalm CX: Its Form Meaning and Purpose." In Studies in the Bible: Presented to Professor M.H. Segal by His Colleagues and Students. Edited by J. M. Grintz & J. Liver. Jerusalem: Published for the Israel Society for Biblical: 17-31.

- Emadi, Matthew. 2022. The Royal Priest: Psalm 110 in Biblical Theology. New Studies in Biblical Theology. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press.

- Fokkelman, J. P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Hermeneutics and Structural Analysis. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum.

- Gentry, Peter J. 2021. “Psalm 110:3 and Retrieval Theology.” Southern Baptist Theological Journal 25, no. 3: 149–168.

- Gilbert, Maurice, and Stephen Pisano. 1980. "Psalm 110 (109), 5-7." Biblica 61, no. 3: 343–56.

- Goldingay, John. 2008. Psalms 90-150. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

- Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm. 1867. Commentary on the Psalms. Vol III. 4th ed. Edinburg: T&T Clark.

- Hilber, John W. 2005. Cultic Prophecy in the Psalms. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 2011. Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101-150. Edited by Klaus Baltzer. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1871. Die Psalmen. Vol. 4. Gotha: F.A. Perthes.

- Jenni, Ernst. 2000. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 3: Die Präposition Lamed. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Lugt, Pieter Van der. 2013. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90–150 and Psalm 1. Vol. 3. Oudtestamentische Studiën 63. Leiden: Brill.

- Mitchell, David C. 2003. The Message of the Psalter: An Eschatological Programme in the Book of Psalms. 2nd ed. Glasgow Scotland: Campbell Publishers.

- Nissinen, Martti, C. L. Seow, Robert K. Ritner, and H. Craig Melchert. 2019. Prophets and Prophecy in the Ancient Near East. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

- Nordheim, Miriam von. 2008. Geboren von der Morgenröte? Psalm 110 in Tradition, Redaktion und Rezeption. Wissenschaftliche Monographien zum Alten und Neuen Testament. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener.

- Olshausen, Justus. Die Psalmen. Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1853.

- Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the First Book of Psalms: Chapter 1-41. 2009. Translated and annoted by H. Norman Strickman. Boston: Academic Studies Press.

- Reinke, Laurenz. 1857. Die messianischen Psalmen; Einleitung, Grundtext und Uebersetzung nebst einem philologisch-kritischen und historischen Commentar. Gießen: Ferber.

- Rogland, Max. 2003. Alleged Non-Past Uses of Qatal in Classical Hebrew. Assen, The Netherlands: Royal van Gorcum.

- SAA Online — State Archives of Assyria Online.

- Stec, David M. 2004. The Targum of Psalms: Translated, with A Critical Introduction, Apparatus, and Notes. Collegeville: Liturgical Press.

- Taylor, Richard, George Kiraz, and Joseph Bali. 2020. The Psalms According to the Syriac Peshitta Version with English Translation. 1st ed. Gorgias Press.

- Tov, Emanuel. 2022. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. 4th edition. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Waltke, Bruce K., J. M. Houston, and Erika Moore. 2010. The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co.

Footnotes

- ↑ Hilber 2005, 82.

- ↑ Zenger 2011, 143; cf. Goldingay 2008.

- ↑ Cf. Reinke 1857, 256.

- ↑ Barbiero 2014, 3.

- ↑ Mitchell 2003, 263; cf. Baethgen 1904; Briggs 1907; Allen 2002; Nordheim 2008.

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.

- ↑ Cf. BHRG 47.2.1, "activating an identifiable entity in order to comment on different entities that are involved in the same situation" (e.g., 2 Sam. 13:19); cf. Lunn: "MKD" (2006, 327).

- ↑ So Lunn 2006, 327, "MKD".

- ↑ Cf. von Nordheim 2008; see Story Behind.

- ↑ GKC 164f, citing Ps. 110:1; cf. BDB עד II:1b; Delitzsch; Baethgen 1904, 337; Görg, "Thronen zur Rechten Gottes," 1996, 76.

- ↑ Cf. Gen. 28:15; 49:10; Deut. 7:24.

- ↑ Smyth 2383.

- ↑ BHRG 40.38; for על כן + yiqtol in the Psalms, see Ps. 1:5; 18:50; 25:8; 42:7; 45:18; 46:3.