Psalm 110 Poetry

About the Poetics Layer

Exploring the Psalms as poetry is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language. This layer is comprised of two main parts: Poetic Structure and Poetic Features.

Poetic Structure

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into strophes, strophes into stanzas, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Macro-structure

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Notes

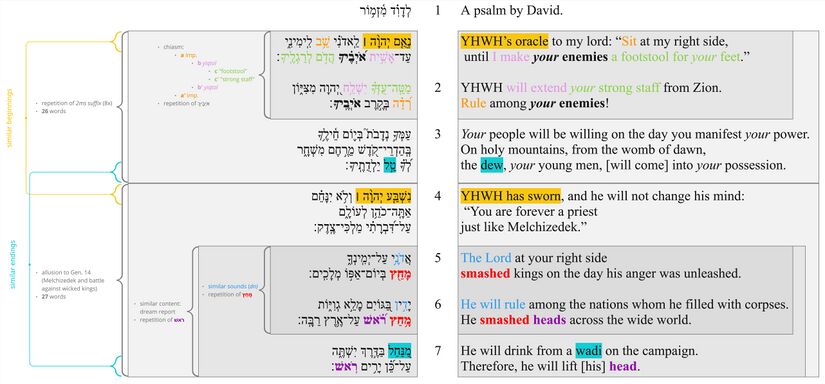

- The psalm consists of two sections (vv. 1-3 // vv. 4-7).

- Each section has a similar beginning.

- YHWH's name + quotative frame + direct speech: נְאֻ֤ם יְהוָ֨ה ׀ (v. 1) // נִשְׁבַּ֤ע יְהוָ֨ה ׀ (v. 4).

- Verse 1 and v. 4 are almost identical in terms of their prosodic structures according to the Masoretic accents.

- Each section has a similar ending.

- The first section ends with the mention of "dew" (v. 3), and the second section ends with the mention of a "wadi" (v. 7). Both "dew" and a "wadi" are sources of water that give refreshment.

- The two sections are of similar lengths (26 words // 27 words).

- The first section (vv. 1-3) is bound together by the repetition of the 2ms suffix, which occurs 8 times in this section (as apposed to one time in the second section) and multiple times in each verse.

- The second section (vv. 4-7) is bound together by the psalm's allusion to Gen. 14. Like Genesis 14, Ps. 110 features Melchizedek (cf. v. 4) and describes a battle against wicked kings (cf. vv. 5-7).

- Each section has a similar beginning.

- The first two verses are bound together as a unit by the repetition of the word אֹיְבֶיךָ (vv. 1b, 2b) and by a chiasm: a imperative, b yiqtol, c "footstool" // c' "strong staff", b' yiqtol, a' imperative.

- Verses 5-6 are similarly bound together into a unit by the repetition of the rare word מחץ and by the similar sounds with which each verse begins: אֲדֹנָ֥י and יָדִ֣ין both have the consonants d and n.

- Verse 7 is added to vv. 5-6 to form a larger unit. The grouping of v. 7 with vv. 5-6 is supported by the repetition of the word רֹאשׁ (vv. 6b, 7b) and the fact that vv. 5-7 seem to describe a single scene, a dream report in which YHWH, like a warrior, crushes his enemies and refreshes himself with a drink.

- Verse 3 and v. 4, though they belong to different sections, are juxtaposed in the centre of the psalm. They are the only two tricola in the psalm and thus bear some resemblance to one another.

Line Divisions

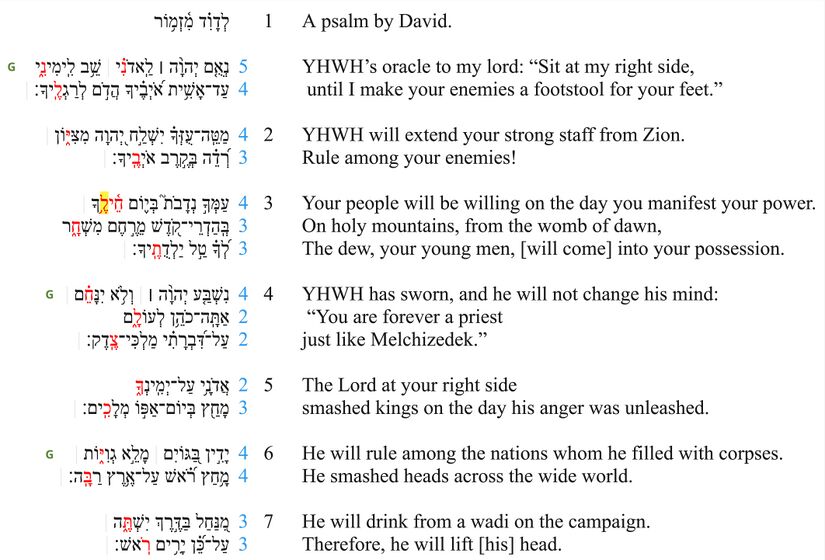

Line division divides the poem into lines and line groupings. We determine line divisions based on a combination of external evidence (Masoretic accents, pausal forms, manuscripts) and internal evidence (syntax, prosodic word counting and patterned relation to other lines). Moreover, we indicate line-groupings by using additional spacing.

When line divisions are uncertain, we consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. Then, if a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences our decision to divide the text at a certain point, we place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

| Poetic line division legend | |

|---|---|

| Pausal form | Pausal forms are highlighted in yellow. |

| Accent which typically corresponds to line division | Accents which typically correspond to line divisions are indicated by red text. |

| | | Clause boundaries are indicated by a light gray vertical line in between clauses. |

| G | Line divisions that follow Greek manuscripts are indicated by a bold green G. |

| DSS | Line divisions that follow the Dead Sea Scrolls are indicated by a bold green DSS. |

| M | Line divisions that follow Masoretic manuscripts are indicated by a bold green M. |

| Number of prosodic words | The number of prosodic words are indicated in blue text. |

| Prosodic words greater than 5 | The number of prosodic words if greater than 5 is indicated by bold blue text. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Notes

The line division proposed above is identical to the division in the 13th century Babylonian manuscript Or 2373.

- v. 1. Some scholars parse v. 1 into four lines (e.g., BHS, Fokkelman, van der Lugt, von Nordheim). A line break between שֵׁ֥ב לִֽימִינִ֑י and נְאֻ֤ם יְהוָ֨ה ׀ לַֽאדֹנִ֗י may supported by by the Masoretic accentuation (revia gadol following a precursor; cf. Sanders and de Hoop 2022); the Aleppo Codex also has a space between these clauses. Other manuscripts, however, present שֵׁ֥ב לִֽימִינִ֑י נְאֻ֤ם יְהוָ֨ה ׀ לַֽאדֹנִ֗י as a single line and the entire verse as a bicolon (LXX mss, Codex Amiatimus, Babylonian ms Or2373). This latter division is probably correct, because (1) it is supported by the oldest manuscript traditions, (2) bicola are generally far more common than tetracola, and (3) there are quite a few examples of bicola in which the a-line contains a quotative frame and the beginning of the direct speech, which is then resumed and concluded in the b-line (Pss. 10:6, 11; 68:23; 91:2; Job 10:2; 34:5, 9; Prov. 22:13; 26:13).

- v. 4. It is difficult to decide whether v. 4 consists of three or two lines. The MT accents suggest three lines (cf. Sanders and de Hoop 2022), which is how the text is divided in the Aleppo Codex, the Babylonian ms Or2373, and the Codex Amiatinus (so also van der Lugt and Fokkelman). A division into two lines, however, is supported by the LXX mss, by the syntax—v. 4bc is one clause—and by the word count—2 lines would yield a balanced 4/4 structure.

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

Claimed and Confirmed

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

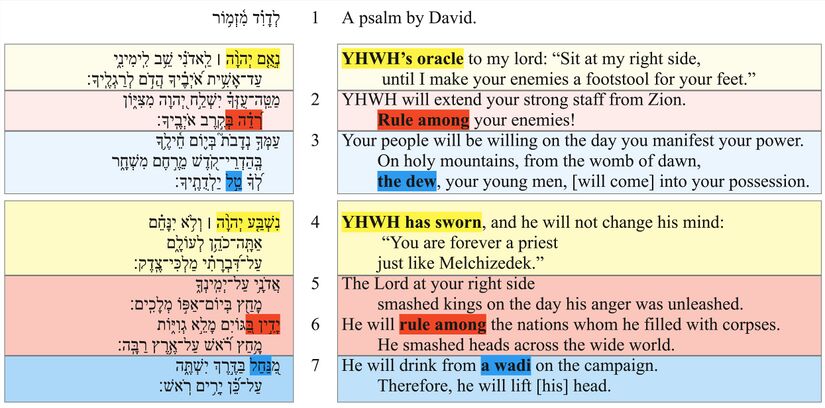

The psalm is structured in two parallel halves (vv. 1-3 // vv. 4-7).

Both halves begin (v. 1 // v. 4) by quoting YHWH's speech according to a similar pattern: quotative frame beginning with נ + divine name + quoted speech. In the middle of both halves (v. 2 // vv. 5-6), the psalmist reflects on YHWH's speech in the previous verses (vv. 1, 4) and describes the extent of the king's dominion over his enemies, referring to "rule" (with different words) over enemies. Both halves conclude (v. 3 // v. 7) by mentioning a nourishing water source: "dew" (v. 3) and "wadi" (v. 7).

But the two halves of the psalm are also different in some important respects. The second half of the psalm not only corresponds to the first half, it also carries its meaning forward. In the first half, YHWH invites the king to sit at his right hand (v. 1), and in the second half, YHWH confirms the king's special status with an unchanging oath (v. 4). In the first half, the psalmist assures the king that YHWH will extend his dominion so that he rules among his enemies (v. 2), and in the second half (vv. 5-6), the psalmist describes these same events in much more graphic language. In the first half, the psalmist assures the king that his army gathered before the battle will be like dew (v. 3), and in the second half he says that after the battle, YHWH will drink from the enemy's wadi, thus confirming his complete conquest.

Effect

If the purpose of the psalm is "to assure the king of his certain success" (see Speech Act Analysis), then the psalmist accomplishes this goal through patterned repetition. After assuring the king, in vv. 1-3, that he has a special status (v. 1), that YHWH will extend his dominion (v. 2), and that he will have military victory (v. 3), the psalmist repeats and amplifies all of these points. The king's status is confirmed with an oath (v. 4), the expansion of his dominion is reported in vivid detail (vv. 5-6), and his victory is described from the perspective of its completion (v. 7) rather than its preparation.

The Lord and the lord

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

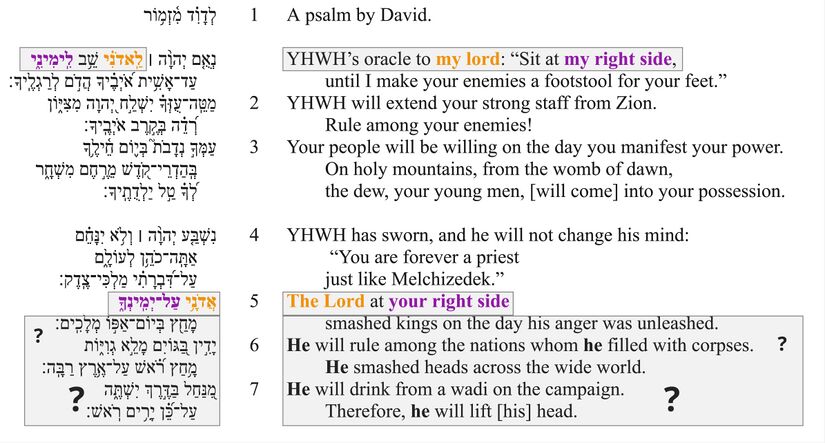

Feature

In v. 1, the king is referred to as "my lord" (אדני), and he is invited to sit at YHWH's "right side" (ימין). In v. 5, YHWH is referred to as "the Lord" (אדני) and is said to be at the king's "right side" (ימין). In both v. 1 and v. 5, the consonantal text אדני is identical, though the Masoretic vowel points distinguish "my lord" (v. 1—אדנִי) from "the Lord" (v. 5—אדנָי).

And not only are these two participants—the lord and the Lord—described in similar terms, but in vv. 5-7 (especially v. 7), it is difficult to determine which of them is the subject. See The Subject(s) in Ps. 110:5-7.

Effect

Even if YHWH is the most likely subject throughout vv. 5-7, the lack of complete clarity on the issue (evident from the variety of interpretations) may be a deliberate feature of the text. As Van der Lugt notes, "it is a basic constituent of the overall framework of the psalm that God and the king are mutually exchangeable;" both are called אדני, and both position themselves at the right hand of the other."[1] Thus, "there seems to be a conflation of YHWH and the king... presumably to stress their oneness of will and purpose."[2] A similar ambiguity of subject and conflation of YHWH and the king takes place in Ps. 2:12.

Pentateuchal Prophecy

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

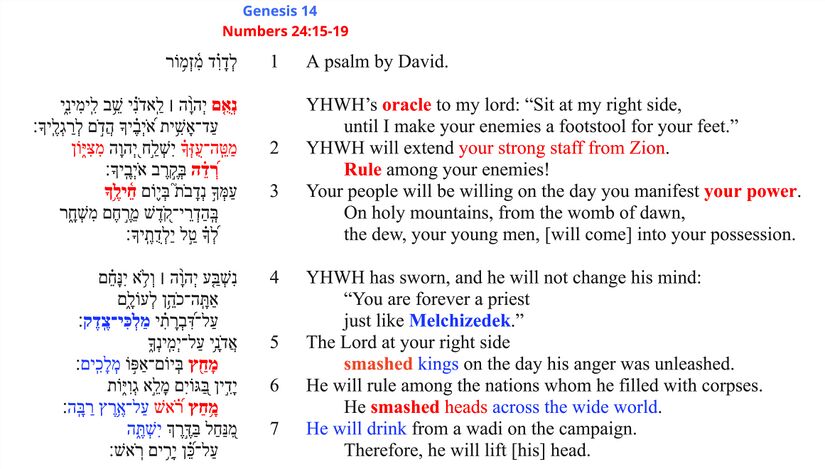

David meditated on the Torah day and night (cf. Ps. 1; Deut. 17). It is no surprise, therefore, that a psalm of David (see superscription) should be filled with allusions to passages in the Torah (cf. allusions to Deut. 33 in Ps. 4). Psalm 110 strongly alludes to two passages in the Torah: Genesis 14 and Numbers 24:15-19.

Genesis 14 is the only other passage in the Hebrew Bible to mention "Melchizedek" (Gen. 14:18; cf. Ps. 110:4). The same chapter also describes a great battle in which kings are defeated across the wide world (cf. Ps. 110:5-6) and which concludes in the victors drinking (Gen. 14:18; cf. Ps. 110:4).

Numbers 24:15-19 is, like Psalm 110, an "oracle" (נְאֻם). and, like Ps. 110, the oracle in Numbers describes a "staff" (שֵׁבֶט) that will come "from Israel" (מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל) (cf. Ps. 110:2a), "smash" (מָחַץ) the heads of his enemies (cf. Ps. 110:5-6) and "rule" (רדה) (cf. Ps. 110:2b). The word חיל ("power") is also used in Numbers 24 (cf. Ps. 110:3).

Effect

Psalm 110 is an oracle—a divine revelation—that develops previous divine revelation. Like the Messianic figure in Balaam's oracle, the king in Ps. 110 will conquer his enemies and "rule" (רדה) from Jacob. Psalm 110 develops the Messianic picture of Numbers 24 by blending it with Genesis 14: the Messiah will be, like Melchizedek, both king and priest in Zion. The characters and events of Genesis 14 are thus read typologically. Just as the coalition of evil kings was defeated across the wide world in the days of Melchizedek, so too when the new "Melchizedek" comes, YHWH (with the king at his side) will conquer the rebellious kings of the earth.

Repeated Roots

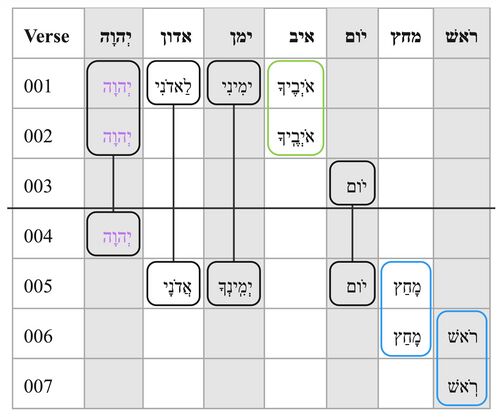

The repeated roots table is intended to identify the roots which are repeated in the psalm.

| Repeated Roots legend | |

|---|---|

| Divine name | The divine name is indicated by bold purple text. |

| Roots bounding a section | Roots bounding a section, appearing in the first and last verse of a section, are indicated by bold red text. |

| Roots occurring primarily in the first section are indicated in a yellow box. | |

| Roots occurring primarily in the third section are indicated in a blue box. | |

| Roots connected across sections are indicated by a vertical gray line connecting the roots. | |

| Section boundaries are indicated by a horizontal black line across the chart. | |

- Repetition of מחץ and ראש in the b-lines of vv. 5-6 seems to bind these verses together, just as the repetition of יהוה and איביך seems to bind together vv. 1-2.

- The following words or combinations of words are repeated in both halves of the psalm: יהוה (v. 1a // v. 4a); אדני + ימין (v. 1a // v. 5); בְּיוֹם (v. 3a // v. 5b)

Repeated Roots Mini-story

Bibliography

- Alan KamYau, Chan. 2016. ”7 A Literary and Discourse Analysis of Psalm 110.” In Melchizedek Passages in the Bible: A Case Study for Inner-Biblical and Inter-Biblical Interpretation, 97-118. Warsaw, Poland: De Gruyter Open Poland.

- Alter, Robert. 2011. The Art of Biblical Poetry. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Barbiero, Gianni. 2014. "The non-violent messiah of Psalm 110". Biblische Zeitschrift 58, 1: 1-20.

- Barthélemy, Dominique. 2005. Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament. Vol. Tome 4: Psaumes. Fribourg, Switzerland: Academic Press.

- Booij, Thijs. 1991. "Psalm Cx: Rule in the Midst of Your Foes!" Vetus Testamentum. Vol. 41, no.: 396-407.

- Bratcher, Robert G. and William David Reyburn. 1991. A Translator’s Handbook on the Book of Psalms. UBS Handbook Series. New York: United Bible Societies.

- Briggs, Charles and Emilie Briggs. 1907. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. International Critical Commentary. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.

- Caquot, André. 1956. "Remarques sur le Psaume CX." Semitica. Vol. 6: 33-52.

- de Hoop, Raymond, and Paul Sanders. 2022. “The System of Masoretic Accentuation: Some Introductory Issues”. The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 22.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1877. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms: Vol. 3. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Driver, G. R. 1964. "Psalm CX: Its Form Meaning and Purpose." In Studies in the Bible: Presented to Professor M.H. Segal by His Colleagues and Students. Edited by J. M. Grintz & J. Liver. Jerusalem: Published for the Israel Society for Biblical: 17-31.

- Emadi, Matthew. 2022. The Royal Priest: Psalm 110 in Biblical Theology. New Studies in Biblical Theology. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press.

- Fokkelman, J. P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Hermeneutics and Structural Analysis. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum.

- Gentry, Peter J. 2021. “Psalm 110:3 and Retrieval Theology.” Southern Baptist Theological Journal 25, no. 3: 149–168.

- Gilbert, Maurice, and Stephen Pisano. 1980. "Psalm 110 (109), 5-7." Biblica 61, no. 3: 343–56.

- Goldingay, John. 2008. Psalms 90-150. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

- Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm. 1867. Commentary on the Psalms. Vol III. 4th ed. Edinburg: T&T Clark.

- Hilber, John W. 2005. Cultic Prophecy in the Psalms. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 2011. Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101-150. Edited by Klaus Baltzer. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1871. Die Psalmen. Vol. 4. Gotha: F.A. Perthes.

- Jenni, Ernst. 2000. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 3: Die Präposition Lamed. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Lugt, Pieter Van der. 2013. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90–150 and Psalm 1. Vol. 3. Oudtestamentische Studiën 63. Leiden: Brill.

- Mitchell, David C. 2003. The Message of the Psalter: An Eschatological Programme in the Book of Psalms. 2nd ed. Glasgow Scotland: Campbell Publishers.

- Nissinen, Martti, C. L. Seow, Robert K. Ritner, and H. Craig Melchert. 2019. Prophets and Prophecy in the Ancient Near East. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

- Nordheim, Miriam von. 2008. Geboren von der Morgenröte? Psalm 110 in Tradition, Redaktion und Rezeption. Wissenschaftliche Monographien zum Alten und Neuen Testament. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener.

- Olshausen, Justus. Die Psalmen. Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1853.

- Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the First Book of Psalms: Chapter 1-41. 2009. Translated and annoted by H. Norman Strickman. Boston: Academic Studies Press.

- Reinke, Laurenz. 1857. Die messianischen Psalmen; Einleitung, Grundtext und Uebersetzung nebst einem philologisch-kritischen und historischen Commentar. Gießen: Ferber.

- Rogland, Max. 2003. Alleged Non-Past Uses of Qatal in Classical Hebrew. Assen, The Netherlands: Royal van Gorcum.

- SAA Online — State Archives of Assyria Online.

- Stec, David M. 2004. The Targum of Psalms: Translated, with A Critical Introduction, Apparatus, and Notes. Collegeville: Liturgical Press.

- Taylor, Richard, George Kiraz, and Joseph Bali. 2020. The Psalms According to the Syriac Peshitta Version with English Translation. 1st ed. Gorgias Press.

- Tov, Emanuel. 2022. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. 4th edition. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Waltke, Bruce K., J. M. Houston, and Erika Moore. 2010. The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co.