Psalm 18 Discourse

About the Discourse Layer

Our Discourse Layer includes four additional layers of analysis:

- Participant analysis

- Macrosyntax

- Speech act analysis

- Emotional analysis

For more information on our method of analysis, click the expandable explanation button at the beginning of each layer.

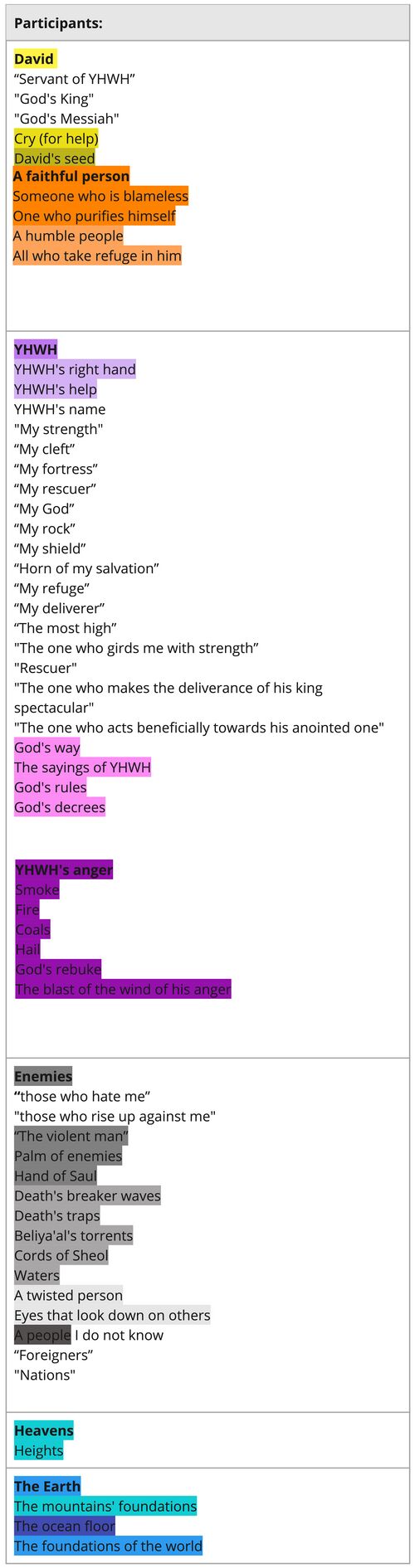

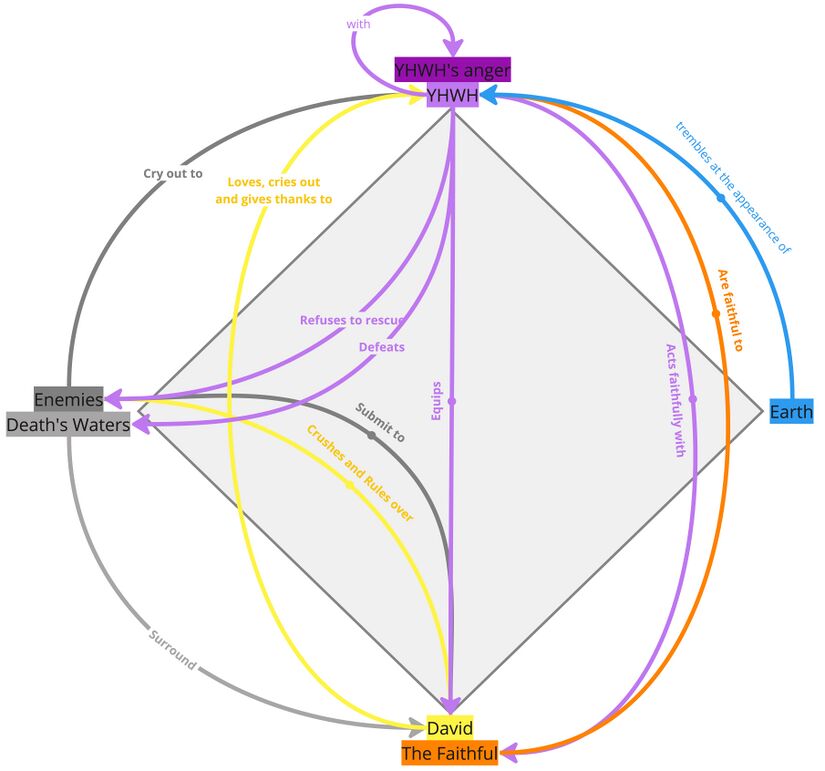

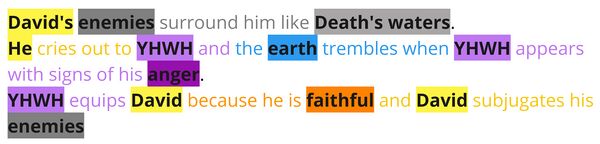

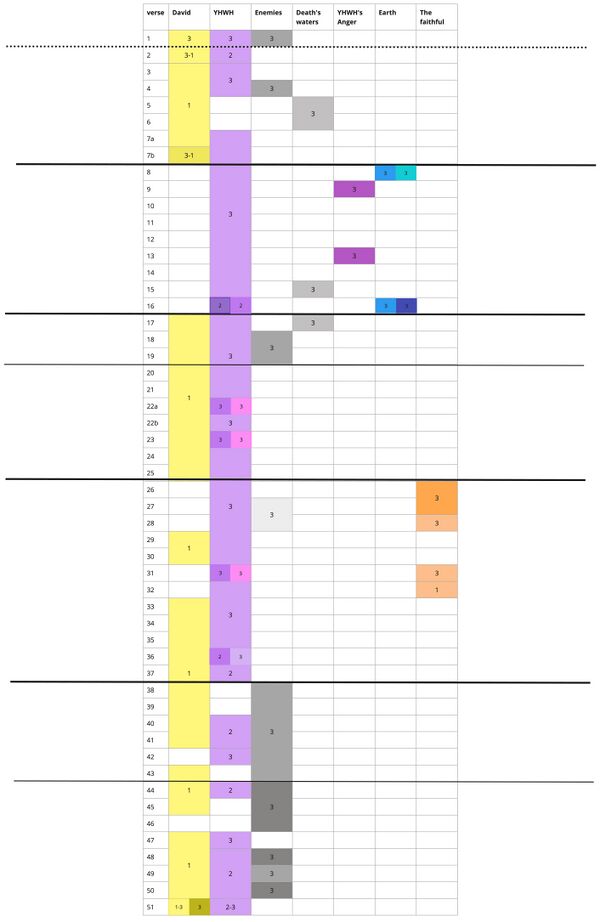

Participant Analysis

Participant Analysis focuses on the characters in the psalm and asks, “Who are the main participants (or characters) in this psalm, and what are they saying or doing? It is often helpful for understanding literary structure, speaker identification, etc.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Participant Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Participant Relations Diagram

The relationships among the participants may be abstracted and summarized as follows:

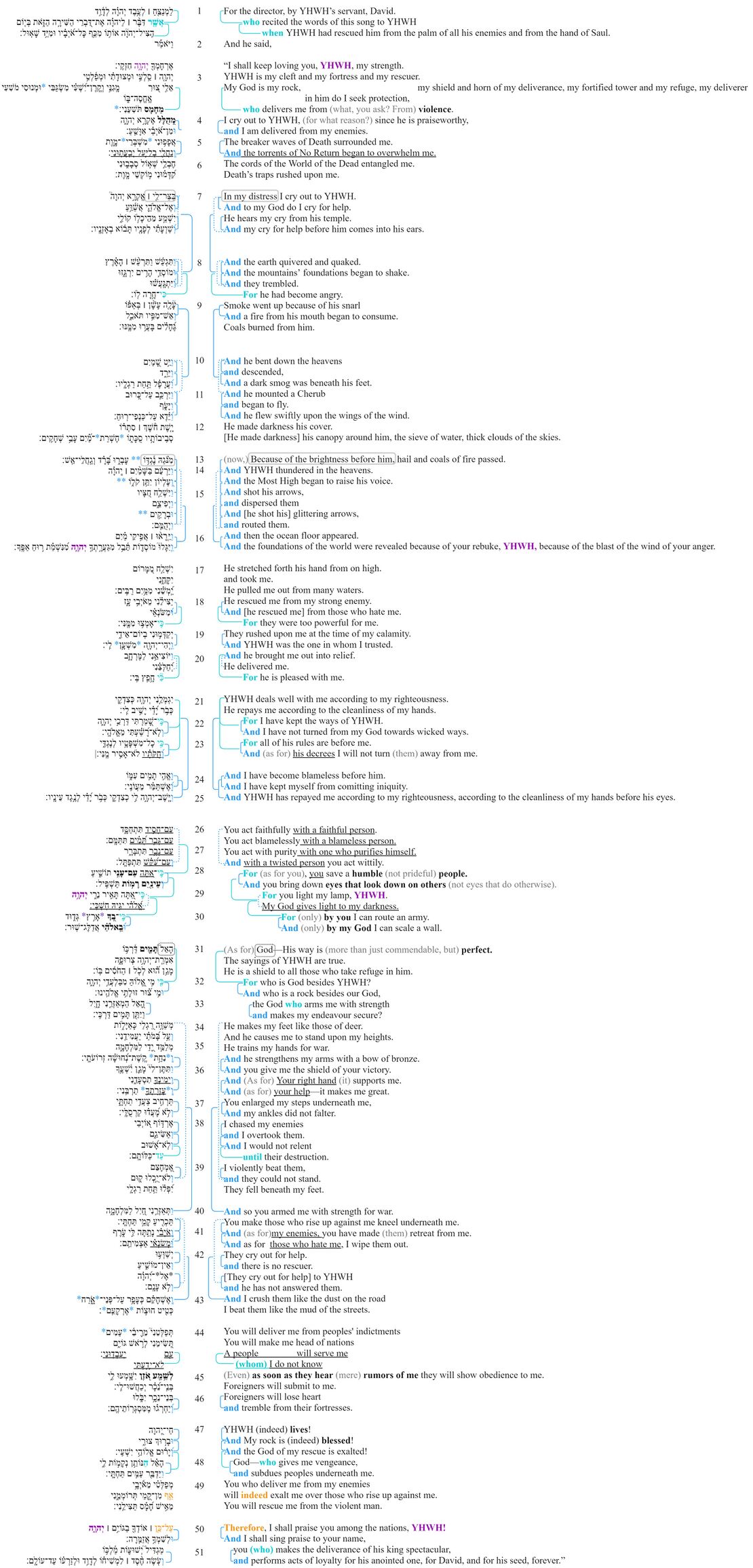

Macrosyntax

The macrosyntax layer rests on the belief that human communicators desire their addressees to receive a coherent picture of their message and will cooperatively provide clues to lead the addressee into a correct understanding. So, in the case of macrosyntax of the Psalms, the psalmist has explicitly left syntactic clues for the reader regarding the discourse structure of the entire psalm. Here we aim to account for the function of these elements, including the identification of conjunctions which either coordinate or subordinate entire clauses (as the analysis of coordinated individual phrases is carried out at the phrase-level semantics layer), vocatives, other discourse markers, direct speech, and clausal word order.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Macrosyntax Creator Guidelines.

Macrosyntax Diagram

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[1] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[2] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

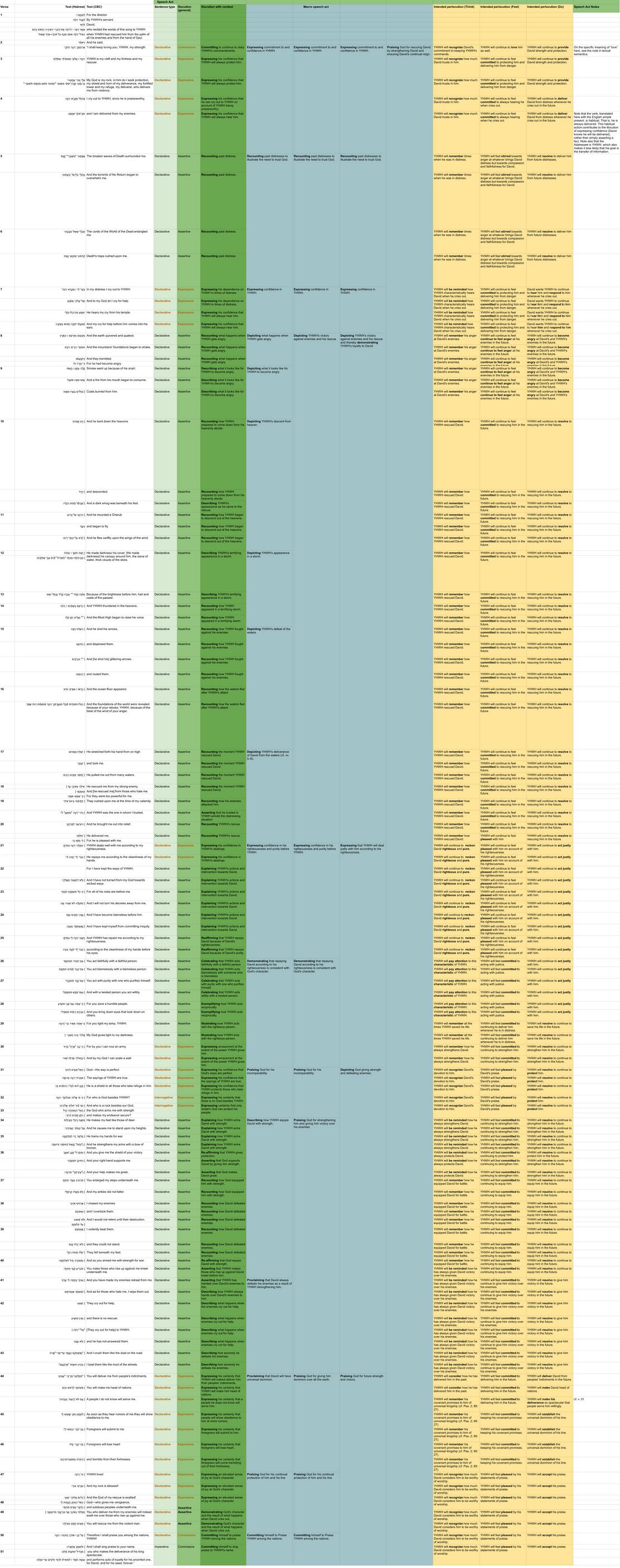

Speech Act Analysis

The Speech Act layer presents the text in terms of what it does, following the findings of Speech Act Theory. It builds on the recognition that there is more to communication than the exchange of propositions. Speech act analysis is particularly important when communicating cross-culturally, and lack of understanding can lead to serious misunderstandings, since the ways languages and cultures perform speech acts varies widely.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Speech Act Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Summary Visual

Speech Act Chart

The following chart is scrollable (left/right; up/down).

| Verse | Hebrew | CBC | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) |

| Verse number and poetic line | Hebrew text | English translation | Declarative, Imperative, or Interrogative Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

Assertive, Directive, Expressive, Commissive, or Declaratory Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

More specific illocution type with paraphrased context | Illocutionary intent (i.e. communicative purpose) of larger sections of discourse These align with the "Speech Act Summary" headings |

What the speaker intends for the address to think | What the speaker intends for the address to feel | What the speaker intends for the address to do |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

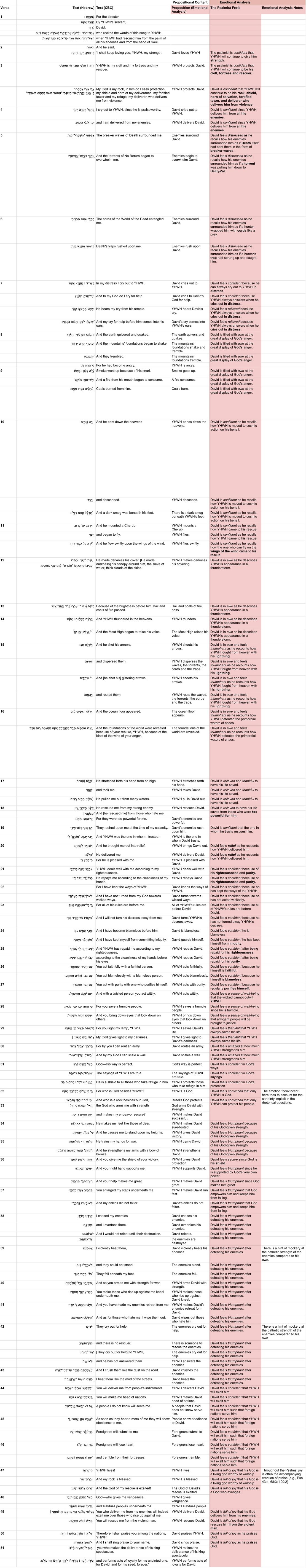

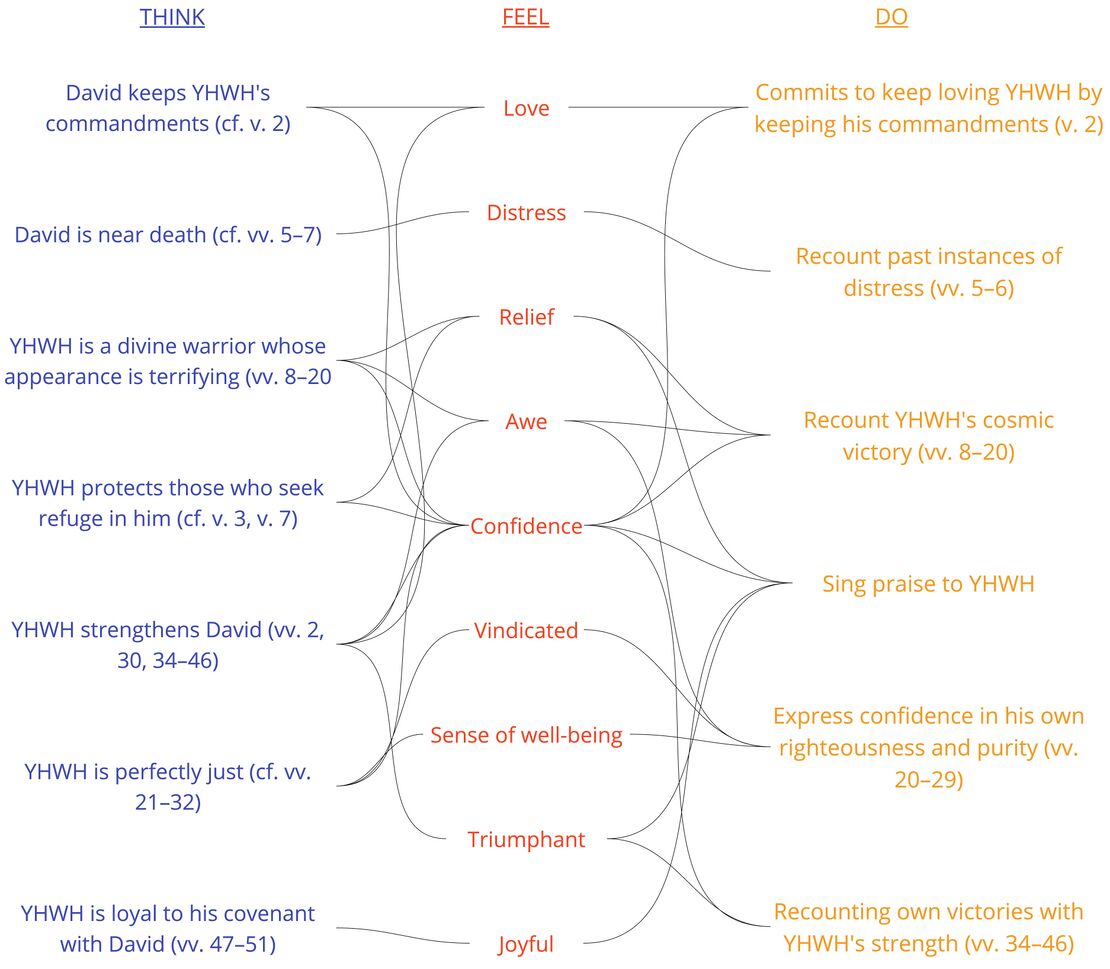

Emotional Analysis

This layer explores the emotional dimension of the biblical text and seeks to uncover the clues within the text itself that are part of the communicative intent of its author. The goal of this analysis is to chart the basic emotional tone and/or progression of the psalm.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Emotional Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Emotional Analysis Chart

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Summary Visual

Bibliography

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. https://archive.org/details/diepsalmen00baet.

- Baillet, Maurice. 1962. “8Q2. Psautier.” In Les “petites grottes” de Qumrân, 148–49, plate XXXI. DJD 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Barthélemy, Dominique. 2005. Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament: Tome 4. Psaumes. Vol. 4. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Bekins, Peter. Forthcoming. “Definiteness” in The Oxford Grammar of Biblical Hebrew.

- Briggs, Charles A. and Emilie Grace Briggs. 1906–1907. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

- Brooke, Aland England, and Norman McLean, eds. 1906. The Old Testament in Greek.Volume II The Later Historical Books Part I. I and II Samuel. Vol. I,1. London: Cambridge University Press. http://archive.org/details/OldTestamentGreeklxxTextCodexVaticanus.

- Carbajosa, Ignacio. 2020. “10.3.4 Peshitta”, in: Textual History of the Bible, General Editor Armin Lange. Consulted online on 14 April 2021

- Charlesworth, James et. al. 2000. Miscellaneous Texts from the Judaean Desert. DJD XXXVIII. Oxford: Claredon Press.

- Chazon, Esther et. al. 1999. Qumran Cave 4 XX: Poetical and Liturgical Texts, Part 2. DJD XXIX. Oxford: Claredon Press.

- Clines, Davd J.A. 1989. Job 1–20. Word Biblical Commentary vol. 17. Dallas: Word.

- Cohen, Chaim. 1995. “The Basic Meaning of the Term ערפל ‘Darkness.’” Hebrew Studies 36 (1): 7–12.

- Comrie, Bernard. 1985. Tense. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139165815.

- Cowe, S. Peter. First published online: 2020. “3–5.2.5.3 1–2 Samuel (1–2 Reigns)”, in: Textual History of the Bible, General Editor Armin Lange. Consulted online on 15 September 2022.

- Craigie, Peter C. 2004. Psalm 1–50. 2nd edition. Word Biblical Commentary vol. 19. Nashville, TN: Nelson Reference & Electronic.

- Crenshaw, James L. 1972. “We Dōrēk ’al-Bāmŏtê ’Āreṣ.” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 34 (1): 39–53.

- Croft, William. 2022. Morphosyntax: Constructions of the World’s Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cross, Frank Moore. 1975. Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry. Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press for the Society of Biblical Literature. http://archive.org/details/studiesinancient0000cros.

- Cross, Frank Moore et. al. 2005. Qumran Cave 4 XII 1–2 Samuel. DJD XVII. Oxford: The Claredon Press.

- Cross, Frank Moore, and David Noel Freedman. 1953. “A Royal Song of Thanksgiving: II Samuel 22 = Psalm 18.” Journal of Biblical Literature 72 (1): 15–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3261627.

- Fabry, Heinz-Josef. 2003. “צַר (1),” ed. G. Johannes Botterweck and Helmer Ringgren, trans. Douglas W. Stott, Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

- Fassberg, Stephen. 2020. “כלום יש מ"ם אנקליטית בלשון המקרא?” In סוגיות בלשון המקרא, edited by Michael Rijke, 87–104. Jerusalem: Academy of the Hebrew Language.

- Fernández Marcos, Natalio. 2013. “The Antiochene Edition in the Text History of the Greek Bible.” In Der Antiochenische Text Der Septuaginta in Seiner Bezeugung Und Seiner Bedeutung, edited by Siegfried Kreuzer and Marcus Sigismund, 57–73. De Septuaginta Investigationes. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666536083.57.F

- Fernández Marcos, Natalio, and José Ramón Busto Saiz. 1989. El texto antioqueno de la Biblia Griega. 1: 1-2 Samuel. Textos y estudios Cardenal Cisneros de la Biblia Políglota Matritense 50. Madrid: Inst. de Filología.

- Gray, Alison Ruth. 2014. In Psalm 18 in Words and Pictures. Leiden: Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/23722.

- Greenfield, Jonas C. 1958. “Lexicographical Notes I.” Hebrew Union College Annual 29:203–28.

- Gordis, Robert. 1971. The Biblical Text in the Making: A Study of the Kethib-Qere. Brooklyn: Ktav Publishing House.

- Hardy, H.H. 2022. The Development of Biblical Hebrew Prepositions. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press.

- Haspelmath, Martin. 2007. “Further Remarks on Reciprocal Constructions.” In Reciprocal Constructions, edited by Vladimir P. Nedjalkov, 2087–2115. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Holmstedt, Robert D. 2016. The Relative Clause in Biblical Hebrew. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781575064208.

- Holmstedt, Robert D. 2020. “Parenthesis in Biblical Hebrew as Noncoordinative Nonsubordination.” Brill’s Journal of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 12 (1): 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1163/18776930-01201003.

- Hope, Edward R. 2003. All Creatures Great and Small: Living Things in the Bible. New York: United Bible Societies.

- Huddleston, Rodney D., and Geoffrey K. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://archive.org/details/cambridgegrammar0000hudd.

- Huehnergard, John, and Aren M. Wilson-Wright. 2014. “A Compound Etymology for Biblical Hebrew Zûlātî ‘Except.’” Hebrew Studies 55. https://www.academia.edu/9939183/2014_A_Compound_Etymology_for_Biblical_Hebrew_z%C3%BBl%C4%81t%C3%AE_except_.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1855. Die Psalmen. Vol. 1. Gotha: Friedrich Andreas Perthes.

- Jenni, Ernst. 1992. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 1: Die Präposition Beth. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Jenni, Ernst. 2000. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 3: Die Präposition Lamed. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Kauhanen, Tuuka, and Pessoa da Silva Pinto. 2020. “Recognizing Kaige-Readings in Samuel-Kings.” Journal of Septuagint and Cognate Studies 53:67–86.

- Keel, Othmar. 1997. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Keil, Carl Friedrich and Franz Delitzsch. 1996. Commentary on the Old Testament. Volume 5. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson.

- Khan, Geoffrey. Forthcoming. “Yiqṭol” in The Oxford Grammar of Biblical Hebrew.

- Kruger, Paul A. 2015. “Emotions in the Hebrew Bible: A Few Observations on Prospects and Challenges.” Old Testament Essays 28 (2): 395–420. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/V28N2A10.

- Kutscher, Edward Yechezkel. 1974. The Language and Linguistic Background of the Isaiah Scroll (I Q Isa[Superscript a]). Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah, v. 6. Leiden: Brill.

- Kogan, Leonid. 2015. Genealogical Classification of Semitic: The Lexical Isoglosses. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614515494.

- Martínez, Florentino García; Tigchellar, Eibert J.C. and Van der Woude, Adam S. 1998. Qumran Cave 11 II: 11Q2–18, 11Q20–31. DJD 23. Oxford, Claredon Press.

- May, Herbert G. 1955. “Some Cosmic Connotations of Mayim Rabbîm, ‘Many Waters.’” Journal of Biblical Literature 74 (1): 9–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/3261949.

- McCarter, P. Kyle. 1973. “The River Ordeal in Israelite Literature.” Harvard Theological Review 66 (4): 403–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0017816000018101.

- McCarter Jr., P. Kyle. 1984. 1 Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Vol. 8. The Anchor Bible. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company.

- McCarter Jr., P. Kyle. 1984. 1 Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Vol. 8. The Anchor Bible. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company.

- Miller, Cynthia L. 2003. “A Linguistic Approach to Ellipsis in Biblical Poetry: (Or, What to Do When Exegesis of What Is There Depends on What Isn’t).” Bulletin for Biblical Research 13 (2): 251–70.

- Morrison, Craig E. 2020. “3–5.1.4 Peshitta”, in: Textual History of the Bible, General Editor Armin Lange. Leiden: Brill.

- Noegel, Scott. 2017. “On the Wings of the Winds: Towards an Understanding of Winged Mischwesen in the Ancient Near East.” KASKAL 14:15–54.

- Notarius, Tania. 2017. “Playing with Words and Identity: Reconsidering לָרִב בָּאֵשׁ, אֲנָךְ, and קֵץ/קַיִץ in Amos’ Visions.” Vetus Testamentum 67 (1): 59–86. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685330-12341264.

- Pinker, Aron. 2005. “On the Meaning of השוחנ תשק.” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 5.

- Rahlfs, Alfred. 1931. Psalmi Cum Odis. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. http://archive.org/details/PsalmiCumOdis.

- Reinhart, Tanya. 1984. “Principles of gestalt perception in the temporal organization of narrative texts.” Linguistics 22.779-809.

- Robar, Elizabeth. 2014. The Verb and the Paragraph in Biblical Hebrew: A Cognitive-Linguistic Approach. Leiden: Brill.

- Sanders, Paul. 2000. “Ancient Colon Delimitations: 2 Samuel 22 and Psalm 18.” In Delimitation Criticism: A New Tool in Biblical Scholarship, edited by Marjo Korpel and Josef Oesch, 277–311. Leiden: Brill

- Sperling, S. David. 2017. Ve-Eileh Divrei David: Essays in Semitics, Hebrew Bible and History of Biblical Scholarship. Leiden: Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/25209.

- Stec, David. 2020. “10.3.3 Targum”, in: Textual History of the Bible, General Editor Armin Lange. Consulted online on 14 April 2021

- Sutcliffe, E. F. 1953. “The Clouds as Water-Carriers in Hebrew Thought.” Vetus Testamentum 3 (1): 99–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/1516291.

- Ulrich, Eugene Charles. 1978. The Qumran Text of Samuel and Josephus. Leiden: Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/39176.

- Walton, John. H. 2009. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary (Old Testament): The Minor Prophets, Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

- Wevers, J.W. 1995. Notes on the Greek Text of Deuteronomy. SCS 39. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press.

- Wilson, Daniel. 2021. “הָיָה in Biblical Hebrew.” In Semitic Languages and Cultures, edited by Aaron D. Hornkohl and Geoffrey Khan, 1st ed., 7:455–72. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0250.16.

- Young, Theron. 2005. “Psalm 18 and 2 Samuel 22: Two Versions of the Same Song.” In Seeking Out the Wisdom of the Ancients: Essays Offered to Honor Michael V. Fox on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday, edited by Ronald L. Troxel, Kelvin G. Friebel, and Dennis R. Magary, 53–70. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781575065625-007.

Footnotes

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.