Psalm 33 Story Behind

About the Story Behind Layer

The Story Behind the Psalm shows how each part of the psalm fits together into a single coherent whole. Whereas most semantic analysis focuses on discrete parts of a text such as the meaning of a word or phrase, Story Behind the Psalm considers the meaning of larger units of discourse, including the entire psalm.

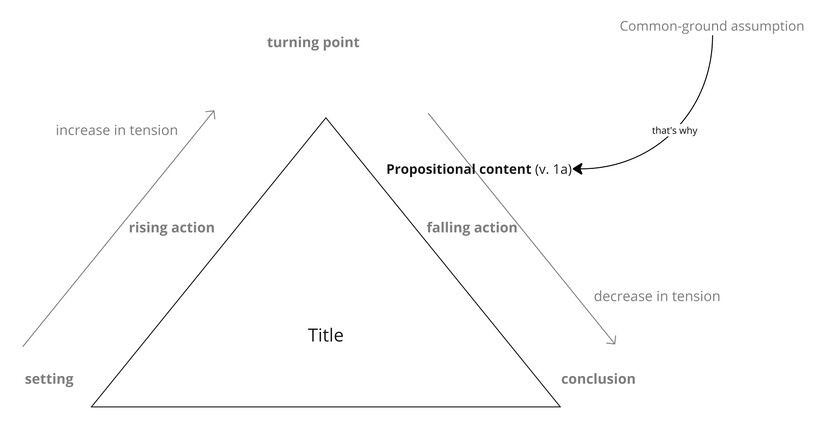

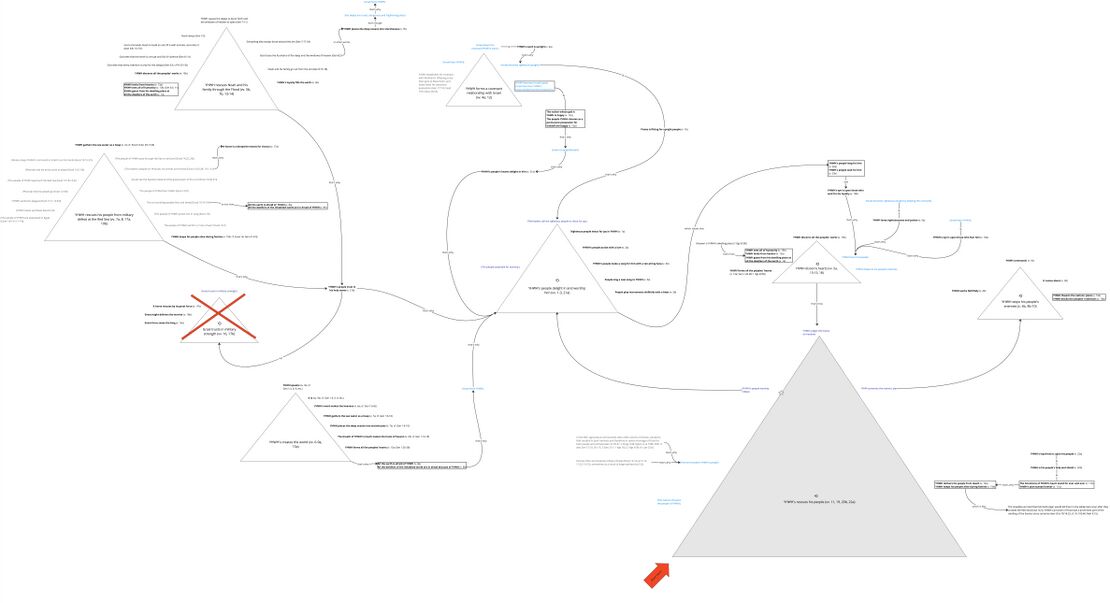

The goal of this layer is to reconstruct and visualise a mental representation of the text as the earliest hearers/readers might have conceptualised it. We start by identifying the propositional content of each clause in the psalm, and then we identify relevant assumptions implied by each of the propositions. During this process, we also identify and analyse metaphorical language (“imagery”). Finally, we try to see how all of the propositions and assumptions fit together to form a coherent mental representation. The main tool we use for structuring the propositions and assumptions is a story triangle, which visualises the rise and fall of tension within a semantic unit. Although story triangles are traditionally used to analyse stories in the literary sense of the word, we use them at this layer to analyse “stories” in the cognitive sense of the word—i.e., a story as a sequence of propositions and assumptions that has tension.

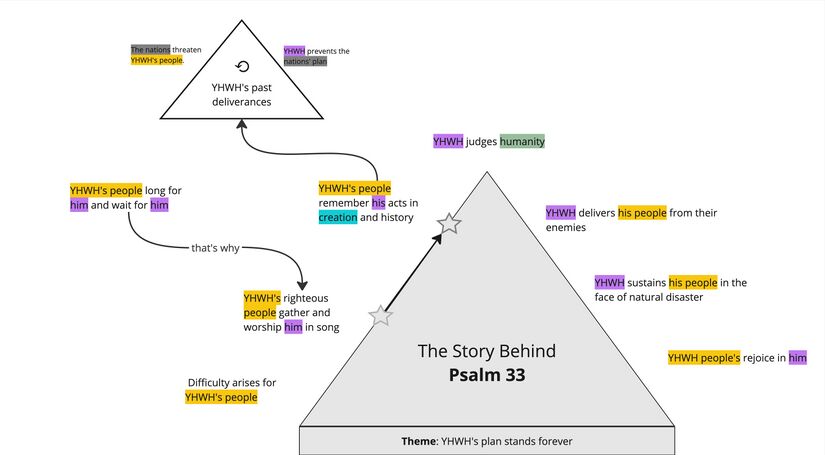

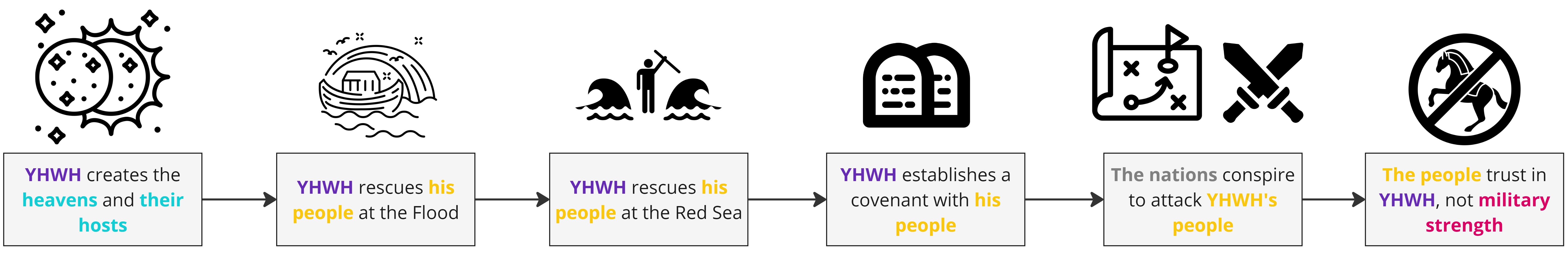

Summary Triangle

The story triangle below summarises the story of the whole psalm. We use the same colour scheme as in Participant Analysis. The star icon along the edge of the story-triangle indicates the point of the story in which the psalm itself (as a speech event) takes place. We also include a theme at the bottom of the story. The theme is the main message conveyed by the story-behind.

| Story Triangles legend | |

|---|---|

| Propositional content (verse number) | Propositional content, the base meaning of the clause, is indicated by bold black text. The verse number immediately follows the correlating proposition in black text inside parentheses. |

| Common-ground assumption | Common-ground assumptions[1] are indicated by gray text. |

| Local-ground assumption | Local-ground assumptions[2] are indicated by dark blue text. |

| Playground assumption | Playground assumptions[3] are indicated by light blue text. |

| The point of the story at which the psalm takes place (as a speech event) is indicated by a gray star. | |

| If applicable, the point of the story at which the psalm BEGINS to take place (as a speech event) is indicated with a light gray star. A gray arrow will travel from this star to the point at which the psalm ends, indicated by the darker gray star. | |

| A story that repeats is indicated by a circular arrow. This indicates a sequence of either habitual or iterative events. | |

| A story or event that does not happen or the psalmist does not wish to happen is indicated with a red X over the story triangle. | |

| Connections between propositions and/or assumptions are indicated by black arrows with small text indicating how the ideas are connected. | |

| Note: In the Summary triangle, highlight color scheme follows the colors of participant analysis. | |

Background ideas

Following are the common-ground assumptionsCommon-ground assumptions include information shared by the speaker and hearers. In our analysis, we mainly use this category for Biblical/Ancient Near Eastern background. which are the most helpful for making sense of the psalm.

- YHWH used his control over the deeps to send and stop the Flood, which was an instrument of his judgment (Gen 7:11, 8:2).

- YHWH saved his people at the Red Sea by piling up the waters as a heap (Exod 15:8; cf Josh 3:13-16); there he threw Egyptian horses and their riders into the sea (Exod 14:23; 15:1, 19, 21).

- YHWH formed a covenant with his people, and if they keep it then he will be their god (Gen 17:7-8) and they will be his treasured possession (Exod 6:7, 19:6, Deut 29:13).

Background situation

The background situation is the series of events leading up to the time in which the psalm is spoken. These are taken from the story triangle – whatever lies to the left of the star icon.

Expanded Paraphrase

The expanded paraphrase seeks to capture the implicit information within the text and make it explicit for readers today. It is based on the CBC translation and uses italic text to provide the most salient background information, presuppositions, entailments, and inferences.

| Expanded paraphrase legend | |

|---|---|

| Close but Clear (CBC) translation | The CBC, our close but clear translation of the Hebrew, is represented in bold text. |

| Assumptions | Assumptions which provide background information, presuppositions, entailments, and inferences are represented in italics. |

There are currently no Imagery Tables available for this psalm.

Bibliography

- Aejmelaeus, Anneli. 1986. “Function and Interpretation of כי in Biblical Hebrew.” JBL 105: 193–209.

- ________. 1993. On the Trail of Septuagint Translators: Collected Essays. Kampen: Kok Pharos Pub. House.

- Anderson, A. A. 1972. The Book of Psalms Volume 1: Psalms 1-72. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- Auffret, Pierre. 2009. "'Rendez Grace a YHWH Avec La Harpe': Etude Structurelle Du Psaume 33." Estudios Bíblicos 67: 85–100.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Bekins, Peter. 2014. "Object Marking in Biblical Hebrew Poetry." SBLSPS 53. San Diego: Society of Biblical Literature.

- Berlin, Adele. 2007. The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- Blau, Joshua. 1976. A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Boda, Mark J. 2010. 1-2 Chronicles. Cornerstone Biblical Commentary 5. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers.

- Bratcher, Robert G., and William D. Reyburn. 1991. A Handbook on Psalms. UBS Handbook Series. New York: United Bible Societies.

- Briggs, Charles A., and Emilie Grace Briggs. 1906. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. ICC. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.

- Calvin, John. 1965. A Commentary on the Psalms. Edited by T.H.L. Parker. Translated by Arthur Golding. Vol. 1. London: Camelot Press.

- Craigie, Peter C. 1983. Psalms 1–50. WBC 19. Dallas: Word.

- Dahood, Mitchell. 1966. Psalms I: 1-50. AB. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- ________. 1966. “Vocative Lamedh in the Psalter.” VT 16, no. 3: 299–311.

- deClaissé-Walford, Nancy, Rolf A. Jacobson, and Beth LaNeel Tanner. 2014. The Book of Psalms. NICOT. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- Deissler, Alfons. 1956. “Der Anthologische Charakter des Psalmes 33 (32).” Pages 225–33 in Mélanges Bibliques: Rédigés en L’Honneur de Andre Robert. Edited by Pierre Casetti et al. Paris: Bloud & Gay.

- Duhm, Bernhard. 1899. Die Psalmen. Kurzer Hand-Commentar Zum Alten Testament 14. Leipzig und Tübingen: Mohr (Paul Siebeck).

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2000. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 2: 85 Psalms and Job 4–14). Vol. 2. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Garr, W. Randall. 2004. “ןה.” Revue Biblique 111:321–44.

- Hallo, William W., and K. Lawson Younger, eds. 2003. The Context of Scripture: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World. Vol. 1. Leiden ; Boston: Brill.

- Hallo, William W., and K. Lawson Younger, eds. 2000. The Context of Scripture: Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World. Vol. 2. Leiden ; Boston: Brill.

- Hendel, Ronald S. 1996. In the Margins of the Hebrew Verbal System: Situation, Tense, Aspect, Mood. Zeitschrift Für Althebraistik 9: 152–81.

- Huehnergard, John. 1983. “Asseverative *la and Hypothetical *lu/Law in Semitic.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103, no. 3: 569–93.

- Humbert, Paul. 1946. La Terou’a: Analyse d’un Rite Biblique. Neuchatel: Université de Neuchatel.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1868. Die Psalmen. Vol. 2. Gotha: Friedrich Andreas Perthes.

- Janzen, Waldemar. 1965. “’Ašrê in the Old Testament.” Harvard Theological Review 58:215–26.

- Keel, Othmar. 1997. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Keil, Carl Friedrich, and Franz Delitzsch. 1996. Commentary on the Old Testament. Peabody: Hendrickson.

- Kennicott, Benjamin. 1775. Vetus Testamentum Hebraicum Cum Variis Lectionibus. Oxford:Clarendon Press.

- Kim, Young Bok. 2023. “Hebrew Forms of Address: A Sociolinguistic Analysis.” Atlanta: SBL Press.

- Kirkpatrick, A. F., ed. 1902. The Book of Psalms. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Kittel, Rudolf. 1922. Die Psalmen. Leipzig: A. Deichertsche Verlagsbuchhandlung Dr. Werner Scholl.

- Kolyada, Yelena. 2013. A Compendium of Musical Instruments and Instrumental Terminology in the Bible. Translated by Yelena Kolyada and David Clark. Abingdon: Routledge.

- König, Ekkehard, and Peter Siemund. 2007. “Speech Act Distinctions in Grammar.” Pages 276–324 in Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Edited by Timothy Shopen. Vol. 1 of 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kraus, Hans-Joachim. 1988. Psalms 1-59: A Commentary. Minneapolis: Augsburg.

- Kugel, James L. 1981. The Idea of Biblical Poetry: Parallelism and Its History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Labuschagne, C.J. 2020 “Numerical Features of the Psalms, a Logotechnical Quantitative Structural Analysis.” DataverseNL.

- Locatell, Christian. 2017. “Grammatical Polysemy in the Hebrew Bible: A Cognitive Linguistic Approach to כי.” PhD Dissertation, University of Stellenbosch.

- Locatell, Christian. 2019. “Causal Categories in Biblical Hebrew Discourse: A Cognitive Approach to Causal כי.” Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 45, no. 2: 79–102.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2006. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: With Special Reference to the First Book of the Psalter. Vol. 1. Oudtestamentische Studiën 53. Leiden: Brill.

- Merrill, Eugene H. 2015. A Commentary on 1 & 2 Chronicles. Kregel Exegetical Library. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic.

- Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. 2010. “Vocative Syntax in Biblical Hebrew Prose and Poetry: A Preliminary Analysis.” Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 36, no. 1: 43–64.

- Murray, Sarah. 2014. “Varieties of Update.” Semantics and Pragmatics 7:1–53.

- Muraoka, Takamitsu. 1985. Emphatic Words and Structures in Biblical Hebrew. Leiden: Brill.

- Niccacci, Alviero. 2006. “The Biblical Hebrew Verbal System in Poetry.” Pages 247–68 in Biblical Hebrew in Its Northwest Semitic Setting: Typological and Historical Perspectives. Edited by Steven E. Fassberg and Avi Hurvitz. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Magnes Press.

- O’Connor, Michael Patrick. 1980. Hebrew Verse Structure. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Podechard, Emmanuel. 1949. Le Psautier: notes critiques: Psaumes 1-75. Vol. 1. Bibliotèque de la Faculté Catholique de Théologie du Lyon 4. Lyon: Facultés Catholiques.

- Ross, Allen P. 2001. Introducing Biblical Hebrew. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

- ________. 2011. A Commentary on the Psalms, Volume 1: 1-41. Kregel Exegetical Library. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic.

- Ryken, Leland, Jim Wilhoit, Tremper Longman, Colin Duriez, Douglas Penney, and Daniel G. Reid, eds. 1998. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

- Stec, David M., ed. 2004. The Targum of Psalms. The Aramaic Bible 16. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press.

- Strickman, H. Norman. 2009. Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the First Book of Psalms. Boston: Academic Studies Press.

- Suderman, W. Derek. May 2015. “The Vocative Lamed and Shifting Address in the Psalms: Reevaluating Dahood’s Proposal.” VT 65, no. 2: 297–312.

- Tate, Marvin E. 1998. Psalms 51–100. WBC 20. Dallas: Word.

- Taylor, Richard A. 2020. The Syriac Peshitta Bible with English Translation. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.

- Vincent, Jean Marcel. 1978. “Recherches Exégétiques Sur Le Psaume 33.” VT 28: 442–54.

- Witte, Markus. 2002. “Das Neue Lied--Beobachtungen Zum Zeitverständnis von Psalm 33” ZAW 114: 522–41.

- Ziegert, Carsten. 2020. “What Is חֶ֫סֶד? A Frame-Semantic Approach.” JSOT 44: 711–32.

Footnotes

- ↑ Common-ground assumptions include information shared by the speaker and hearers. In our analysis, we mainly use this category for Biblical/ANE background - beliefs and practices that were widespread at this time and place. This is the background information necessary for understanding propositions that do not readily make sense to those who are so far removed from the culture in which the proposition was originally expressed.

- ↑ Local-ground assumptions are those propositions which are necessarily true if the text is true. They include both presuppositions and entailments. Presuppositions are those implicit propositions which are assumed to be true by an explicit proposition. Entailments are those propositions which are necessarily true if a proposition is true.

- ↑ Whereas local-ground assumptions are inferences which are necessarily true if the text is true, play-ground assumptions are those inferences which might be true if the text is true.